My father had few enthusiasms, but he loved comedy. He was a comedy nerd, though this is so common a condition in Britain as to be almost not worth mentioning. Like most Britons, Harvey gathered his family around the defunct hearth each night to watch the same half-hour comic situations repeatedly, in reruns and on video. We knew the “Dead Parrot” sketch by heart. We had the usual religious feeling for “Monty Python’s Life of Brian.” If we were notable in any way, it was not in kind but in extent. In our wood-cabinet music center, comedy records outnumbered the Beatles. The Goons’ “I’m Walking Backward for Christmas” got an airing all year long. We liked to think of ourselves as particular, on guard against slapstick’s easy laughs—Benny Hill was beneath our collective consideration. I suppose the more precise term is “comedy snobs.”

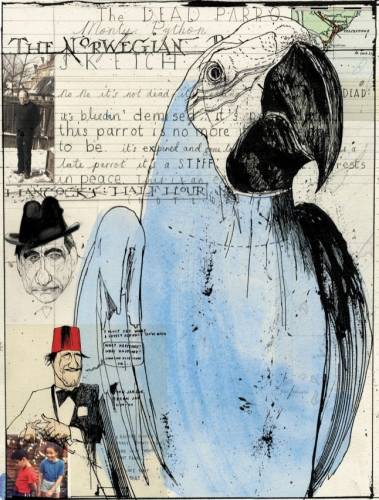

Illustration by David Hughes

Left unchecked, comedy snobbery can squeeze the joy out of the enterprise. You end up thinking of comedy as Hemingway thought of narrative: structured like an iceberg, with all the greater satisfactions fathoms under water, while the surface pleasure of the joke is somehow the least of it. In my father, this tendency was especially pronounced. He objected to joke merchants. He was wary of the revue-style bonhomie of the popular TV double act Morecambe and Wise, and disapproved of the cheery bawdiness of their rivals, the Two Ronnies. He was allergic to racial and sexual humor, to a far greater degree than any of the actual black people or women in his immediate family. Harvey’s idea of a good time was the BBC sitcom “Steptoe and Son,” the grim tale of two mutually antagonistic “rag-and-bone men” who pass their days in a Beckettian pile of rubbish, tearing psychological strips off each other. Each episode ends with the son (a philosopher manqué, who considers himself trapped in the filthy family business) submitting to a funk of existential despair. The sadder and more desolate the comedy, the better Harvey liked it.

His favorite was Tony Hancock, a comic wedded to despair, in his life as much as in his work. (Hancock died of an overdose in 1968.) Harvey had him on vinyl: a pristine, twenty-year-old set of LPs. The series was “Hancock’s Half Hour,” a situation comedy in which Hancock plays a broad version of himself and, to my mind, of my father. A quintessentially English, poorly educated, working-class war veteran with social and intellectual aspirations, whose fictional address—23 Railway Cuttings, East Cheam—perfectly conjures the aspirant bleakness of London’s suburbs (as if Cheam were significant enough a spot to have an East.) Harvey, meanwhile, could be found in 24 Athelstan Gardens, Willesden Green (a poky housing estate named after the ancient king of England), also by a railway. Hancock’s heartbreaking inability to pass as a middle-class beatnik or otherwise pull himself out of the hole he was born in was a source of great mirth to Harvey, despite the fact that this was precisely his own situation. He loved Hancock’s hopefulness, and loved the way he was always disappointed. He passed this love on to his children, with the result that we inherited the comic tastes of a previous generation. (Born in 1925, Harvey was old enough to be our grandfather.) Occasionally, I’d lure friends to my room and make them listen to “The Blood Donor” or “The Radio Ham.” This never went well. I demanded complete silence, was in the habit of lifting the stylus and replaying a section if any incidental noise should muffle a line, and generally leached all potential pleasure from the exercise with laborious explanations of the humor and said humor’s possible obfuscation by period details: ration books, shillings and farthings, coins for the meter, and so on. It was a hard sell in the brave new comedic world of “The Jerk” and “Beverly Hills Cop” and “Ghostbusters.”

Hancock wasn’t such an anachronism, as it turns out. Genealogically speaking, Harvey had his finger on the pulse of British comedy, for Hancock begot Basil Fawlty, and Fawlty begot Alan Partridge, and Partridge begot the immortal David Brent. And Hancock and his descendants served as a constant source of conversation between my father and me, a vital link between us when, class-wise, and in every other wise, each year placed us farther apart. As in many British families, it was university wot dunnit. When I returned home from my first term at Cambridge, we couldn’t discuss the things I’d learned, about Anna Karenina, or G. E. Moore, or Gawain and his staggeringly boring Green Knight, because Harvey had never learned them—but we could always speak of Basil. It was a conversation that lasted decades, well beyond the twelve episodes in which Basil himself is contained. The episodes were merely jumping-off points; we carried on compulsively creating Basil long after his authors had stopped. Great situation comedy expands in the imagination. For my generation, never having seen David Brent’s apartment in “The Office” is no obstacle to conjuring up his interior decoration: the risqué Athena poster, the gigantic entertainment system, the comical fridge magnets. Similarly, for my father, imagining Basil Fawlty’s school career was a creative exercise. “He would have failed his eleven-plus,” Harvey once explained to me. “And that would’ve been the start of the trouble.” When meditating on the sitcom, you extrapolate from the details, which in Britain are almost always signifiers of social class: Hancock’s battered homburg, Fawlty’s cravat, Partridge’s driving gloves, Brent’s fake Italian suits. It’s a relief to be able to laugh at these things. In British comedy, the painful class dividers of real life are neutralized and exposed. In my family, at least, it was a way of talking about things we didn’t want to talk about.

When Harvey was very ill, in the autumn of 2006, I went to visit him at a nursing home in the seaside town of Felixstowe, armed with the DVD boxed set of “Fawlty Towers.” By this point, he was long divorced from my mother, his second divorce, and was living alone on the gray East Anglian coast, far from his children. A dialysis patient for a decade (he lost his first kidney to stones, the second to cancer), his body now began to give up. I had meant to leave the DVDs with him, something for the empty hours alone, but when I got there, with nothing to talk about, we ended up watching them together for the umpteenth time, he on the single chair, me on the floor, cramped in that grim little nursing-home bedroom, surely the least funny place he’d ever found himself in—with the possible exception of the 1944 Normandy landings. We watched several episodes, back to back. We laughed. Never more than when Basil thrashed an Austin 1100 with the branch of a tree, an act of inspired pointlessness that seemed analogous to our own situation. And then we watched the DVD extras, in which we found an illuminating little depth charge hidden among the nostalgia and the bloopers:

It was probably—may have been—my idea that she should be a bit less posh than him, because we couldn’t see otherwise what would have attracted them to each other. I have a sort of vision of her family being in catering on the south coast, you know, and her working behind a bar somewhere, he being demobbed from his national service and getting his gratuity, you know, and going in for a drink and this . . . barmaid behind the bar and she fancied him because he was so posh. And they sort of thought they’d get married and run a hotel together and it was all a bit sort of romantic and idealistic, and the grim reality then caught up with them.

That is the actress Prunella Scales answering a question of comic (and class) motivation that had troubled my father for twenty years: why on earth did they marry each other? A question that—given his own late, failed marriage to a Jamaican girl less than half his age—must have had a resonance beyond the laugh track. On finally hearing an answer, he gave a sigh of comedy-snob satisfaction. Not long after my visit, Harvey died, at the age of eighty-one. He had told me that he wanted “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” played at his funeral. When the day came, I managed to remember that. I forgot which version, though (sweet, melodic Baez). What he got instead was jeering, post-breakup Dylan, which made it seem as if my mild-mannered father had gathered his friends and family with the particular aim of telling them all to fuck off from beyond the grave. As comedy, this would have raised a half smile out of Harvey, not much more. It was a little broad for his tastes.

In birth, two people go into a room and three come out. In death, one person goes in and none come out. This is a cosmic joke told by Martin Amis. I like the metaphysical absurdity it draws out of the death event, the sense that death doesn’t happen at all—that it is, in fact, the opposite of a happening. There are philosophers who take this joke seriously. To their way of thinking, the only option in the face of death—in facing death’s absurd non-face—is to laugh. This is not the bold, humorless laugh of the triumphant atheist, who conquers what he calls death and his own fear of it. No: this is more unhinged. It comes from the powerless, despairing realization that death cannot be conquered, defied, contemplated, or even approached, because it’s not there; it’s only a word, signifying nothing. It’s a truly funny laugh, of the laughor-you’ll-cry variety. There is “plenty of hope, an infinite amount of hope—but not for us!” This is a cosmic joke told by Franz Kafka, a wisecrack projected into a void. When I first put the partial cremains of my father in a Tupperware sandwich box and placed it on my writing desk, that was the joke I felt like telling.

“Why didn’t you spring for a proper G.P.S.?”

Conversely, the death we speak of and deal with every day, the death that is full of meaning, the non-absurd death, this is a place-marker, a fake, a convenient substitute. It was this sort of death that I was determined to press upon my father, as he did his dying. In my version, Harvey was dying meaningfully, in linear fashion, within a scenario stage-managed and scripted by the people around him. Neatly crafted, like an American sitcom: “The One in Which My Father Dies.” It was to conclude with a real event called Death, which he would experience and for which he would be ready. I did all the usual, banal things. I brought a Dictaphone to his bedside, in order to collect the narrative of his life (this perplexed him—he couldn’t see the through line). I grew furious with overworked nurses. I refused to countenance any morbidity from my father, or any despair. The funniest thing about dying is how much we, the living, ask of the dying; how we beg them to make it easy on us. At the hospital, I ingratiated myself with the doctors and threw what the British call “new money” at the situation. Harvey watched me go about my business with a puzzled half smile. To all my eager suggestions he said, “Yes, dear—if you like,” for he knew well that we were dealing with the National Health Service, into which all Smiths are born and die, and my new money would mean only that exactly the same staff, in the same hospital, would administer the same treatments, though in a slightly nicer room, with a window and possibly a television. He left me to my own devices, sensing that these things made a difference to me, though they made none to him: “Yes, dear—if you like.” I was still thrashing an Austin 1100 with a tree branch; he was some way beyond that. And then, when he was truly beyond it, far out on the other side of nowhere, a nurse offered me the opportunity to see the body, which I refused. That was a mistake. It left me suspended in a bad joke in which a living man inexplicably becomes two pints of dust and everyone acts as if this were not a joke at all but, rather, the most reasonable thing in the world. A body would have been usefully, concretely absurd. I would have known—or so people say—that the thing lying there on the slab wasn’t my father. As it was, I missed the death, I missed the body, I got the dust, and from these facts I tried to extrapolate a story, as writers will, but found myself, instead, in a kind of stasis. A moment in which nothing happened, and keeps not happening, forever. Later, I was informed, by way of comfort, that Harvey had also missed his death: he was in the middle of a sentence, joking with his nurse. “He didn’t even know what hit him!” the head matron said, which was funny, too, because who the hell does?

Proximity to death inspired the manic spirit of carpe diem in the Smiths. After Harvey died, my mother met a younger man in Africa and married him. The younger of my two brothers, Luke, went to Atlanta to pursue dreams of rap stardom. Both decisions sounded like promising pilot episodes for new sitcoms. And then I tried to ring in the changes, by moving to Italy. In my empty kitchen, on the eve of leaving the country, I put my finger in the dust of my father and put the dust into my mouth and swallowed it, and there was something very funny about that—I laughed as I did it. After that, it felt as if I didn’t laugh again for a long time. Or do much of anything. Imagined worlds moved quite out of my reach, seemed utterly pointless, not to mention a colossal human presumption: “Yes, dear—if you like.” For two years in Rome, I looked from blank computer screen to handful of dust and back again—a scenario that no one, even in Britain, could turn into a sitcom. Then, as I was preparing to leave Italy, Ben, my other brother, rang with his news. He wanted me to know that he had broken with our long-standing family tradition of passive comedy appreciation. He had decided to become a comedian.

It turns out that becoming a comedian is an act of instantaneous self-creation. There are no intermediaries blocking your way, no gallerists, publishers, or distributors. Social class is a non-issue; you do not have to pass your eleven-plus. In a sense, it would have been a good career for our father, a creative man whose frequent attempts at advancement were forever thwarted, or so he felt, by his accent and his background, his lack of education, connections, luck. Of course, Harvey wasn’t, in himself, funny—but you don’t always have to be. In the world of comedy, if you are absolutely determined to stand on a stage for five minutes with a mike in your hand, someone in London will let you do it, if only once. Ben was determined: he’d given up the after-school youth group he had, till then, managed; he’d written material; he had tickets for me, my mother, my aunt. It was my private opinion that he’d had a minor nervous breakdown of some kind, a delayed reaction to his bereavement. I acted pleased, bought a plane ticket, flew over. We had been tight as thieves as children, but I’d barely seen him since Harvey died, and I sensed us settling into the attenuated relations of adult siblings, a new formal distance, always slightly abashed, for there seems no clear way, in adult life, to do justice to the intimacy of childhood. I remember being scandalized, as a child, at how rarely our parents spoke to their siblings. How was it possible? How did it happen? Then it happens to you. Thinking of him standing up there alone with a microphone, though, trying to be funny, I felt a renewed, Siamese-twin closeness: fearing for him was like fearing for me. I’ve never been able to bear watching anyone die onstage, never mind a blood relative. If he’d told me that it was major heart surgery he was about to have, on this makeshift stage in the tiny, dark basement of a London pub, I couldn’t have been more sick about it.

It was a mixed bill. Before Ben, two men and two women performed a mildewed sketch show of unmistakable Oxbridge vintage, circa 1994. A certain brittle poshness informed their exaggerated portraits of high-strung secretaries, neurotic piano teachers, absent-minded professors. They put on mustaches and wigs and walked in and out of imaginary scenarios where fewer and fewer funny things occurred. It was the comedy of things past. The girls, though dressed as girls, were no longer girls, and the boys had paunches and bald spots; the faintest trace of ancient intracomedy-troupe love affairs clung to them sadly; all the promising meetings with the BBC had come and gone. This was being done out of pure friendship now, or the memory of friendship. As I watched the unspooling horror of it, a repressed, traumatic memory resurfaced, of an audition, one that must have taken place around the time this comedy troupe was formed, very likely in the same town. This audition took the form of a breakfast meeting, a “chat about comedy” with two young men, then members of the Cambridge Footlights, now a popular British TV double act. I don’t remember what it was that I said. I remember only strained smiles, the silent consumption of scrambled eggs, a feeling of human free fall. And the conclusion, which was obvious to us all. Despite having spent years at the grindstone of comedy appreciation, I wasn’t funny. Not even slightly.

And now the compère was calling my brother’s name. He stepped out. I felt a great wash of East Anglian fatalism, my father’s trademark, pass over to me, its new custodian. Ben was dressed in his usual urban streetwear, the only black man in the room. I began peeling the label off my beer bottle. I sensed at once the way he was going to play it, the same way we had played it throughout our childhood—a few degrees off whatever it was that people expected of us, when they looked at us. This evening, that strategy took the form of an opening song about the Olympics, with particular attention paid to equestrian dressage. It was funny! He was getting laughs. He pushed steadily forward, a slow, gloomy delivery that owed something to Harvey’s seemingly infinite pessimism. No good can come of this. This had been Harvey’s reaction to all news, no matter how objectively good that news might be, from the historic entrance of a Smith child into an actual university to the birthing of babies and the winning of prizes. When he became ill, he took a perversely British satisfaction in the diagnosis of cancer: absolutely nothing good could come of this, and the certainty of it seemed almost to calm him.

I waited, like my father, for the slipup, the flat joke. It didn’t come. Ben did a minute on hip-hop, a minute on his baby daughter, a minute on his freshly minted standup career. Another song. I was still laughing, and so was everyone else. Finally, I felt able to look up from the beer mats to the stage. Up there I saw my brother, who is not eight, as I forever expect him to be, but thirty, and who appeared completely relaxed, as if born with mike in hand. And then it was over—no one had died.

The next time I saw Ben do standup was about ten gigs later, at the 2008 Edinburgh Festival Fringe. He didn’t exactly die the night I turned up, but he was badly wounded. It was a shock to him, because it was the first time. In comedy terms, his cherry got popped. At first, he couldn’t see why: it was the same type of venue he’d been doing in London—intimate, drunken—and, by and large, it was the same material. Why, this time, were the laughs smaller? Why, for one good joke in particular, did they not occur at all? We repaired to the bar to regroup, with all the other comedians doing the same. In comedy, the analysis of death, or near-death, experiences is a clear, unsentimental process. The discussion is technical, closer to a musician’s self-analysis than to a writer’s: this note was off; you missed the beat there. I knew I could say to Ben, honestly, and without fear of hurting him, “It was the pause—you went too slowly on the punch line,” and he could say, “Yep,” and the next night the pause would be shortened, the punch line would hit its mark. We ordered more beer. “The thing I don’t understand—I don’t understand what happened with the new material. I thought it was good, but . . . ” Another comedian, who was also ordering beer, chipped in, “Did you do it first?” “Yes.” “Don’t do the new stuff first. Do it last. Just because you’re excited by it doesn’t mean it should go first. It’s not ready yet.”

We drank a lot, with a lot of very drunk comedians, until very late. Trying to keep up with the wisecracks and the complaints, I felt as if I’d arrived late to a battleground that had seen bloody action. The comedians had the aura of survivors, speaking the language of mutual, hard experience: venues too hot and too small, the horror of empty seats, who got nominated for what, who’d been reviewed well or badly, and, of course, the financial pain. (Some Edinburgh performers break even, most incur debts, and almost no one makes a profit.) It was strange to see my brother, previously a member of my family, becoming a member of this family, all his previous concerns and principles subsumed, like theirs, into one simple but demanding question: Is it funny? And that’s another reason to envy comedians: when they look at a blank page, they always know, at least, the question they need to ask themselves. I think the clarity of their aim accounts for a striking phenomenon, peculiar to comedy: the possibility of extremely rapid improvement. Comedy is a Lazarus art; you can die onstage and then rise again. It’s not unusual to see a mediocre young standup in January and, seeing him again in December, discover a comedian who’s found his groove, a transformed artist, a death-defier.

Russell Kane, a relatively new British comic, is a death-defier, the sort of comedian who won’t let a moment pass without filling it with laughter. I went to see him on the last night of his Edinburgh run. His show was called “Gaping Flaws,” a phrase lifted from a negative online review of his 2007 Edinburgh show, which, in turn, was called “Easy Cliché and Tired Stereotype,” a phrase lifted from a negative review of his début 2006 show, “Russell Kane’s Theory of Pretension.” All these reviews came from the same man, Steve Bennett, a prominent British comedy critic who writes for the Web site Chortle. The problem with Kane was class—the British problem. A self-defined working-class “Essex boy” (though, physically, his look is more indie Americana than English suburbia; he’s a dead ringer for the singer Anthony Kiedis), he centers his act on the tricky business of being the alien in the family, the wannabe intellectual son of a working-class, bigoted father. To his father, Kane’s passion for reading is deeply suspicious, his interest in the arts tantamount to an admission of sexual deviancy. Kane’s dilemma has a natural flip side, a typically British ressentiment for those very people his sensibilities have moved him toward. The middle classes, the Guardianistas (readers of the left-leaning liberal newspaper the Guardian), the smug élites who have made him feel his class in the first place. Can’t go home, can’t leave home: a subject close to my heart.

In 2006, Kane played this material too broadly, overexploiting a natural gift for grotesque physical comedy: his father was a hulking deformed monster, the Guardianistas fey fools, skipping across the stage. In 2007, the chip on his shoulder was still there, but the ideas were better, the portraits more detailed, more refined; he began to find his balance, which is a rare mixture of inspired verbal sparring and effective physical comedy. Third time’s the charm: “Gaping Flaws” had almost none. It was still all about class, but some magical integration had occurred. I couldn’t help being struck by the sense that what it might take a novelist a lifetime to achieve, a bright comedian can resolve in three seasons. (How to present a working-class experience to the middle classes without diluting it. How to stay angry without letting anger distort your work. How to be funny about the most serious things.) [#unhandled_cartoon]

Audiences love death-defiers like Kane. It’s what they pay their money for, after all: laughs per minute. They tend to be less fond of those comedians who have themselves tired of the non-stop laughter and pine for a little silence. I want to call it “comedy nausea.” Comedy nausea is the extreme incarnation of what my father felt: not only is joke-telling a cheap art; the whole business of standup is, in some sense, a shameful cheat. For a comedian of this kind, I imagine it feels like a love affair gone wrong. You start out wanting people to laugh in exactly the places you mean them to laugh, then they always laugh where you want them to laugh—then you start to hate them for it. Sometimes the feeling is temporary. The comedian returns to standup and finds new joy in, and respect for, the art of death-defying. Sometimes, as with Peter Cook (voted, by his fellow-comedians, in a British poll, the greatest comedian of all time), comedy nausea turns terminal, and only the most difficult laugh in the world will satisfy. Toward the end of his life, when his professional comedy output was practically nil, Cook made a series of phone calls to a radio call-in show, using the pseudonym Sven from Swiss Cottage (an area of northwest London), during which he discussed melancholy Norwegian matters in a thick Norwegian accent, arguably the funniest and bleakest “work” he ever did.

At the extreme end of this sensibility lies the anti-comedian. An anti-comedian not only allows death onstage; he invites death up. Andy Kaufman was an anti-comedian. So was Lenny Bruce. Tommy Cooper is the great British example. His comedy persona was “inept magician.” He did intentionally bad magic tricks and told surreal jokes that played like Zen koans. He actually died onstage, collapsing from a heart attack during a 1984 live TV broadcast. I was nine, watching it on telly with Harvey. When Cooper fell over, we laughed and laughed, along with the rest of Britain, realizing only when the show cut to the commercial break that he wasn’t kidding.

There was an anti-comedian at Edinburgh this year. His name was Edward Aczel. You will not have heard of him—neither had I, neither has practically anyone. This was only his second Edinburgh appearance. Maybe it was the fortuitous meeting of my mournful mood and his morbid material, but I thought his show, “Do I Really Have to Communicate with You?,” was one of the strangest, and finest, hours of live comedy I’d ever seen. It started with neither a bang nor a whimper. It didn’t really start. We, the audience, sat in nervous silence in a tiny dark room, and waited. Some fumbling with a cassette recorder was heard, faint music, someone mumbling backstage: “Welcome to the stage . . . Edward Aczel.” Said without enthusiasm. A man wandered out. Going bald, early forties, schlubby, entirely nondescript. He said, “All right?” in a hopeless sort of way, and then decided that he wanted to do the introduction again. He went offstage and came on again. He did this several times. Despair settled over the room. Finally, he fixed himself in front of the microphone. “I think you’ll all recall,” he muttered, barely audible, “the words of Wittgenstein, the great twentieth-century philosopher, who said, ‘If indeed mankind came to earth for a specific reason, it certainly wasn’t to enjoy ourselves.’ ” A long, almost unbearable pause. “If you could bear that in mind while I’m on, I’d certainly appreciate it.” Then, on a large flip chart, the kind of thing an account manager in an Aylesbury marketing agency might swipe from his office (Aczel is, in real life, an account manager for an Aylesbury marketing agency), he began to write with a Magic Marker. It was a list of what not to expect from his show. He went through it with us. There was to be:

No nudity.

No juggling.

No impressions of any well-known people.

No reference to crop circles during the show.

No one will be conceived during the show.

No tackling head-on of any controversial issues. . . .

And finally, and I think most importantly—

No refunds.

I recognized my father’s spirit in this list: No good can come of this. He then told us that he had a box of jigsaw puzzles backstage, for anyone who became dangerously bored. Later, he drew a graph made up of an x-axis, which stood for “TIME,” and a y-axis, for “GOODWILL,” on which he tracked the show’s progress. Point one, low down: “Let’s all go and get a drink—this is pointless.” Point two, slightly higher up: “O.K., carry on, whatever.” Point three, still only halfway up: “We could all be here forever. We think this is great.” He looked at his shoes, then, with mild aggression, at the audience. “We’ll never get to that point,” he said. “It’s just . . . it’ll never happen.” By this time, everyone was laughing, but the laughter was a little crazy, disjointed. It’s a reckless thing, for a comedian, to be this honest with an audience. To say, in effect, “Whatever I do, whatever you do, we’re all going to die.” When it finally came to jokes (“Now we go into the section of the show routinely called ‘material,’ for obvious reasons”), Aczel had a dozen written on his hand, and they were very funny, but by now he had already convinced us that jokes were the least of what could be done here. It was an easy and wonderful thing to believe this show a genuine shambles, saved only by our attention and by chance. (We were mistaken, of course. Every stumble, every murmur, is identical, every night.) In the lobby afterward, calendars were on sale, each month illustrated by impossibly banal photographs of Aczel in bed, washing his face, walking into work, standing in the road. Mine sits on my desk, next to my father in his Tupperware sandwich box. On the cover, Aczel is pictured in a supermarket aisle. The subtitle reads, “Life is endless, until you die”—Edith Piaf. Each month has a message for me. November: “Winter is coming—Yes!” April: “Who cares.” June: “This is not the life I was promised.” There is plenty of hope, an infinite amount of hope—but not for us!

On the last night of the Edinburgh festival, in another small, dark, drunken venue, I waited for my brother to go on. It was about two in the morning. Only comedians were left at the festival; the audiences had all gone home. I feared for him, again—but he did his set, and he killed. He was relaxed. There was nothing riding on his performance; the pause had been fixed. Then a young Australian dude came on and spoke a lot about bottle openers, and he killed, too. Maybe everybody kills at two in the morning. Then the end of the end: one last comedian took the bar stage. This was Andy Zaltzman, a great, tall man with an electrified Einstein hairdo and a cutting, political-satirical act that got its laughs per minute. He set to work, confident, funny, and instantly got heckled, a heckle that was followed by a collective audience intake of breath, for the heckler was Daniel Kitson, a rather shy, whimsical young comedian from Yorkshire who looks like a beardy cross between a fisherman and a geography teacher. Kitson won the Perrier Comedy Award in 2002, at the age of twenty-five, and his gift is for the crafting of exquisite narratives, shows shaped like Alice Munro stories, bathetic and beautiful. A comedy-snob thrill passed through the room. It was a bit like Nick Drake turning up at a James Taylor gig. Kitson goodhumoredly heckled Zaltzman, and Zaltzman heckled back. Their ideas went spiralling down nonsensical paths, collided, did battle, and separated. Kitson busied himself handing out flyers for “Our joint show, tomorrow!,” a show that couldn’t exist, because the festival was over. We all took one. Zaltzman and Kitson got loose; the jokes were everywhere, with everyone, the whole room becoming comedy. There was a kind of hysteria abroad. I looked over at my brother and could see that he’d got this abdominal pain, too, and we were both doubled over, crying, and I wished Harvey were there, and at the same moment I felt something come free in me.

I have to confess to an earlier comic embellishment: my father is no longer in a Tupperware sandwich box. He was, for a year, but then I bought a pretty Italian Art Deco vase for him, completely see-through, so I can see through to him. The vase is posh, and not funny like the sandwich box, but I decided that what Harvey didn’t have much of in life he would get in death. In life, he found Britain hard. It was a nation divided by postcodes and accents, schools and last names. The humor of its people helped make it bearable. You don’t have to be funny to live here, but it helps. Hancock, Fawlty, Partridge, Brent: in my mind, they’re all clinging to the middle rungs of England’s class ladder. That, in large part, is the comedy of their situations.

For eighty-one years, my father was up to the same game, though his situation wasn’t so comical; at least, the living of it wasn’t. Listen, I’ll tell you a joke: his mother had been in service, his father worked on the buses; he passed the grammar-school exam, but the cost of the uniform for the secondary school was outside the family’s budget. No, wait, it gets better: At thirteen, he left school to fill the inkwells in a lawyer’s office, to set the fire in the grate. At seventeen, he went to fight in the Second World War. In the fifties, he got married, started a family, and, finding that he had a good eye, tried commercial photography. His pictures were good, he set up a little studio, but then his business partner stiffed him in some dark plot of which he would never speak. His marriage ended. And here’s the kicker: in the sixties, he had to start all over again, as a salesman. In the seventies, he married for the second time. A new lot of children arrived. The high point was the late eighties, a senior salesman now at a direct-mail company—selling paper, just like David Brent. Finally, the (lower) middle rung! A maisonette, half a garden, a sweet deal with a local piano teacher who taught Ben and me together, two bums squeezed onto the piano stool. But it didn’t last, and the second marriage didn’t last, and he ended up with little more than he had started with. Listening to my first novel, “White Teeth,” on tape, and hearing the rough arc of his life in the character Archie Jones, he took it well, seeing the parallels but also the difference: “He had better luck than me!” The novel was billed as comic fiction. To Harvey, it sat firmly in the laugh-or-you’ll-cry genre. And when that “Fawlty Towers” boxed set came back to me as my only inheritance (along with a cardigan, several atlases, and a photograph of Venice), I did a little of both. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com