When Margaret Atwood was in her twenties, an aunt shared with her a family legend about a possible seventeenth-century forebear: Mary Webster, whose neighbors, in the Puritan town of Hadley, Massachusetts, had accused her of witchcraft. “The townspeople didn’t like her, so they strung her up,” Atwood said recently. “But it was before the age of drop hanging, and she didn’t die. She dangled there all night, and in the morning, when they came to cut the body down, she was still alive.” Webster became known as Half-Hanged Mary. The maiden name of Atwood’s grandmother was Webster, and the family tree can be traced back to John Webster, the fifth governor of Connecticut. “On Monday, my grandmother would say Mary was her ancestor, and on Wednesday she would say she wasn’t,” Atwood said. “So take your pick.”

Atwood made the artist’s pick: she chose the story. She once wrote a vivid narrative poem in the voice of Half-Hanged Mary—in Atwood’s telling, a sardonic, independent-minded crone who was targeted by neighbors “for having blue eyes and a sunburned skin . . . a weedy farm in my own name, / and a surefire cure for warts.” Webster’s grim endurance at the end of the rope (“Most will have only one death. / I will have two.”) grants her a perverse kind of freedom. She can now say anything: “The words boil out of me, / coil after coil of sinuous possibility. / The cosmos unravels from my mouth, / all fullness, all vacancy.” In 1985, Atwood made Webster one of two dedicatees of her best-known novel, “The Handmaid’s Tale,” a dystopian vision of the near future, in which the United States has become a fundamentalist theocracy, and the few women whose fertility has not been compromised by environmental pollution are forced into childbearing. The other dedicatee of “The Handmaid’s Tale” was Perry Miller, the scholar of American intellectual history; Atwood studied under him at Harvard, in the early sixties, extending her knowledge of Puritanism well beyond fireside tales.

Having embraced the heritage of Half-Hanged Mary—and having, at seventy-seven, reached an age at which sardonic independent-mindedness is permissible, and even expected—Atwood is winningly game to play the role of the wise elder who might have a spell up her sleeve. In January, I visited her in her home town of Toronto, and within a few hours of our meeting, while having coffee at a crowded café, she performed what friends know as a familiar party trick. After explaining that she had picked up the precepts of medieval palmistry decades ago, from an art-historian neighbor whose specialty was Hieronymus Bosch, Atwood spent several disconcerting minutes poring over my hands. First, she noted my heart line and the line of my intellect, and what their relative positions revealed about my capacity for getting things done. She wiggled my thumbs, a test for stubbornness. She examined my life line—“You’re looking quite healthy at the moment,” she said, to my relief—then told me to shake my hands out and let them fall into a resting position, facing upward. She regarded them thoughtfully. “Well, the Virgin Mary you’re not,” she said, dryly. “But you knew that.”

Atwood has long been Canada’s most famous writer, and current events have polished the oracular sheen of her reputation. With the election of an American President whose campaign trafficked openly in the deprecation of women—and who, on his first working day in office, signed an executive order withdrawing federal funds from overseas women’s-health organizations that offer abortion services—the novel that Atwood dedicated to Mary Webster has reappeared on best-seller lists. “The Handmaid’s Tale” is also about to be serialized on television, in an adaptation, starring Elisabeth Moss, that will stream on Hulu. The timing could not be more fortuitous, though many people may wish that it were less so. In a photograph taken the day after the Inauguration, at the Women’s March on Washington, a protester held a sign bearing a slogan that spoke to the moment: “make margaret atwood fiction again.”

If the election of Donald Trump were fiction, Atwood maintains, it would be too implausible to satisfy readers. “There are too many wild cards—you want me to believe that the F.B.I. stood up and said this, and that the guy over at WikiLeaks did that?” she said. “Fiction has to be something that people would actually believe. If you had published it last June, everybody would have said, ‘That is never going to happen.’ ” Atwood is a buoyant doomsayer. Like a skilled doctor, she takes evident satisfaction in providing an accurate diagnosis, even when the cultural prognosis is bleak. She attended the Toronto iteration of the Women’s March, wearing a wide-brimmed floppy hat the color of Pepto-Bismol: not so much a pussy hat as the chapeau of a lioness. Among the signs she saw that day, her favorite was one held by a woman close to her own age; it said, “i can’t believe i’m still holding this fucking sign.” Atwood remarked, “After sixty years, why are we doing this again? But, as you know, in any area of life, it’s push and pushback. We have had the pushback, and now we are going to have the push again.”

Unlike many writers, Atwood does not require a particular desk, arranged in a particular way, before she can work. “There’s a good and a bad side to that,” she told me. “If I did have those things, then I would be able to put myself in that fetishistic situation, and the writing would flow into me, because of the magical objects. But I don’t have those, so that doesn’t happen.” The good side is that she can write anywhere, and does so, prolifically. She is equally uninhibited about genre. Atwood’s bibliography runs to about sixty books—novels, poetry, short-story collections, works of criticism, children’s books, and, most recently, a comic-book series about a part-feline, part-avian, part-human superhero called Angel Catbird. She is offhanded about her versatility. “I always wrote more than one type of thing,” she said. “Nobody told me not to.” On one occasion, over tea, she showed me her left hand: it had writing on it. “When all else fails, you do have a surface you can write on,” she said.

Atwood travels frequently, and has often spent months at a time living in foreign countries, sometimes under conditions that a less flexible artist might find impossibly distracting. She started writing “The Handmaid’s Tale” on a clunky rented typewriter while on a fellowship in West Berlin, in 1984. (Orwell was on her mind.) She spent a winter in the remote English village of Blakeney, in Norfolk, where her only means of calling North America was a telephone kiosk that was usually used for storing potatoes, and where the stone-floored cottage in which she wrote was so cold that she developed chilblains on her toes. When her daughter, Jess, who was born in 1976, was eighteen months old, Atwood and her partner, the novelist Graeme Gibson, made a round-the-world trip. After winding through Europe, they visited Afghanistan—a keen student of military history, Atwood wanted to see the terrain where the British had been defeated—as well as India and Singapore. They proceeded to Australia, for the Adelaide Literary Festival, then returned to Canada, via Fiji and Hawaii. They made do with carry-on luggage the whole way. ^^

Home is a mansion in the Annex neighborhood of Toronto, near the university. She and Gibson have lived there for more than thirty years, and a basement office serves as the headquarters of Atwood’s company, O. W. Toad, Ltd. (The whimsical name is an anagram of “Atwood,” but sometimes there are postal inquiries as to the existence of a Mr. Toad.) Atwood does not drive, and, for exercise as well as for efficiency, she likes to walk around her neighborhood; she often encounters en route some friend of a half-century’s standing, and they will stop and discuss the past and future surgeries of loved ones—the inevitable discourse of the septuagenarian. Sometimes she drags a heavy shopping cart, loaded with books, for donation to the local library.

“Let me know when those two kids across the street start crying.”

Atwood is enormously well read, and is an evangelist for books she admires, especially by young writers. When I was visiting, she pressed into my hands “Stay with Me,” a novel by the twenty-nine-year-old Nigerian writer Ayobami Adebayo. Sarah Polley, the Canadian film director and writer, who is a friend of Atwood’s, told me, “Usually, after seeing her, I come home with a full notebook, half in her handwriting and half in mine, of every movie and book I had heard of while talking to her—a full course load.” Polley recently wrote the script for a six-part Netflix adaptation of Atwood’s 1996 novel, “Alias Grace,” which is based on a true-life murder mystery in nineteenth-century rural Canada. The book earned Atwood her third of five Booker Prize nominations.

Atwood is warmly recognized in Toronto, whether she is on the street, in a restaurant, or in the subway. (She once slipped me one of her senior-citizen tickets, with a sly arch of the eyebrow.) Traffic cops nod to her in crosswalks, and every encounter I had with her was interrupted by a supplicant autograph hunter or selfie seeker. She never declined. “In the age of social media, you cannot say no, because you’ll get ‘Mean Margaret Atwood was rude to me in a restaurant,’ ” she told me one lunchtime, after graciously signing yet another young woman’s notebook. (Atwood speaks in a low, ironical monotone but adopts a querulous squeak when impersonating imagined detractors.) She would look striking even if she were not familiar. She owns an array of brightly colored winter coats—jewel red, imperial purple—with faux-fur-trimmed hoods that frame her face, as do her abundant curls of silver hair. She has high cheekbones and an aquiline nose, the kind of features that age has a hard time withering. Her skin is clear and translucent, of the sort that writers of popular Victorian fiction associated with good moral character.

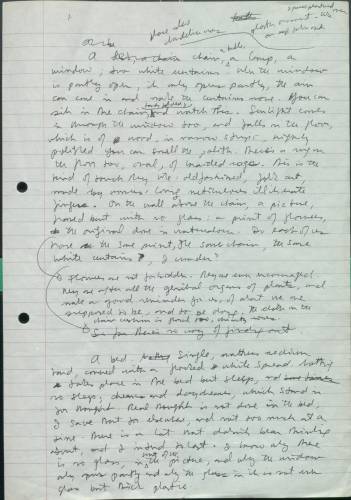

One morning, I accompanied her to the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, at the University of Toronto, where she has donated her archive: four hundred and seventy-four boxes’ worth of papers, so far. She had requested in advance to see materials related to “The Handmaid’s Tale,” and a small study room had been reserved for our use. Boxes had been rolled in on a cart, and one of them contained Atwood’s handwritten draft. On an early page, she describes the plain contours of the room in which Offred, the novel’s narrator, lives—“A chair, a table, a lamp”—though Atwood had not yet refined the detail that, in the published version, gives the opening paragraph of the second chapter a menacing power: “There must have been a chandelier, once. They’ve removed anything you could tie a rope to.” Another box was labelled “Handmaid’s Tale: Background,” and Atwood pried the box open to reveal files containing sheaves of newspaper clippings from the mid-eighties.

1 / 7ChevronChevron

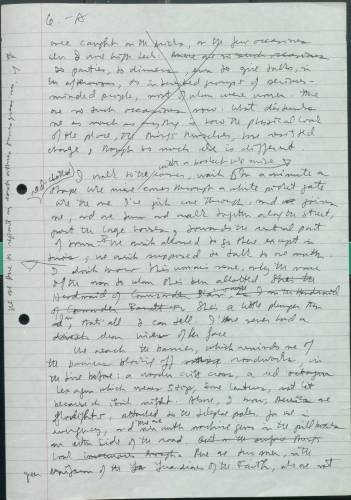

“Clip-clippety-clip, out of the newspaper I clipped things,” she said, as we looked through the cuttings. There were stories of abortion and contraception being outlawed in Romania, and reports from Canada lamenting its falling birth rate, and articles from the U.S. about Republican attempts to withhold federal funding from clinics that provided abortion services. There were reports about the threat to privacy posed by debit cards, which were a novelty at the time, and accounts of U.S. congressional hearings devoted to the regulation of toxic industrial emissions, in the wake of the deadly gas leak in Bhopal, India. An Associated Press item reported on a Catholic congregation in New Jersey being taken over by a fundamentalist sect in which wives were called “handmaidens”—a word that Atwood had underlined.

In writing “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Atwood was scrupulous about including nothing that did not have a historical antecedent or a modern point of comparison. (She prefers that her future-fantasy books be labelled “speculative fiction” rather than “science fiction.” “Not because I don’t like Martians . . . they just don’t fall within my skill set,” she wrote in the introduction to “In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination,” an essay collection that she published in 2011.) The ritualized procreation in the novel—effectively, state-sanctioned rape—is extrapolated from the Bible. “ ‘Behold my maid Bilhah, go in unto her; and she shall bear upon my knees, that I may also have children by her,’ ” Atwood recited. “Obviously, they stuck the two together and out came the baby, and it was given to Rachel. No kidding. It is right there in the text.” In Atwood’s book, the Handmaids are cultivated, like livestock. “I’m taken to the doctor’s once a month, for tests: urine, hormones, cancer smear, blood test,” Offred recounts. “The same as before, except that now it’s obligatory.” Only after completing several chapters does the reader queasily realize that Offred’s innocuous-sounding name is a designation of ownership: the Commander in whose household the narrator serves is named Fred. A decade ago, the book was banned from high schools in San Antonio, Texas, on the ground that it was anti-Christian and excessively explicit about sex. In an open letter to the school district, Atwood pointed out that the Bible has a good deal more to say about sex than her book does, and defended her fiction’s essential truthfulness, speculative or not. “If you see a person heading toward a huge hole in the ground, is it not a friendly act to warn him?” she wrote.

With the novel, she intended not just to pose the essential question of dystopian fiction—“Could it happen here?”—but also to suggest ways that it had already happened, here or elsewhere. While living in West Berlin, Atwood visited Poland, where martial law had only recently been lifted; many dissidents were still in jail. She already knew members of the Polish resistance from the Second World War, who had gone into exile in Canada. “I remember one person saying a very telling thing: ‘Pray you will never have occasion to be a hero,’ ” she said. Atwood’s longtime literary agent, Phoebe Larmore, told me of seeing Atwood during the writing of “The Handmaid’s Tale.” “I had been quite ill that year, and Margaret came and sat on my sofa, and I think she looked worse than I did,” Larmore recalled. “I asked her what was happening. She said, ‘It’s the new novel. It scares me. But I have to write it.’ ”

“The Handmaid’s Tale” became a best-seller, despite some sniffy reviews, like one in the Times, by Mary McCarthy, who wrote, “Even when I try, in the light of these palely lurid pages, to take the Moral Majority seriously, no shiver of recognition ensues.” It has since sold so many millions of copies that Atwood considers them uncountable. Her friend the novelist Valerie Martin was the first to read the finished manuscript; they were both teaching in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. “There is kind of a disagreement about what I said,” Martin told me. “She says that I said, ‘There is something in it.’ But what I think I said is: ‘You are going to be rich.’ ” The book quickly became canonical. Atwood’s daughter was nine when it was published; by the time she was in high school, it was required reading for graduation.

Despite the novel’s current air of timeliness, the contours of the dystopian future that Atwood imagined in the eighties do not map closely onto the present moment—although recent news images of asylum seekers fleeing across the U.S. border into Canada have a chilling resonance with the opening moments of the television series, which shows Moss, not yet enlisted as a Handmaid, attempting to escape from the U.S. to its northern neighbor, where democracy prevails. Still, the U.S. in 2017 does not show immediate signs of becoming Gilead, Atwood’s imagined theocratic American republic. President Trump is not an adherent of traditional family values; he is a serial divorcer. He is not known to be a man of religious faith; his Sundays are spent on the golf course.

What does feel familiar in “The Handmaid’s Tale” is the blunt misogyny of the society that Atwood portrays, and which Trump’s vocal repudiation of “political correctness” has loosed into common parlance today. Trump’s vilification of Hillary Clinton, Atwood believes, is more explicable when seen through the lens of the Puritan witch-hunts. “You can find Web sites that say Hillary was actually a Satanist with demonic powers,” she said. “It is so seventeenth-century that you can hardly believe it. It’s right out of the subconscious—just lying there, waiting to be applied to people.” The legacy of witch-hunting, and the sense of shame that it engendered, Atwood suggests, is an enduring American blight. “Only one of the judges ever apologized for the witch trials, and only one of the accusers ever apologized,” she said. Whenever tyranny is exercised, Atwood warns, it is wise to ask, “Cui bono?” Who profits by it? Even when those who survived the accusations levelled against them were later exonerated, only meagre reparations were made. “One of the keys to America is that your neighbor may be a Communist, a serial killer, or in league with satanic forces,” Atwood said. “You really don’t trust your fellow-citizens very much.”

Now, Atwood argues, women have been put on notice that hard-won rights may be only provisional. “It’s the return to patriarchy,” she said, as she paged through the clippings. “Look at his Cabinet!” she said of Trump. “Look at the kind of laws that people have put through in the states. Absolutely they want to overturn Roe v. Wade, and they will have to deal with the consequences if they do. You’re going to have a lot more orphanages, aren’t you? A lot more dead women, a lot more illegal abortions, a lot more families with children in them left without a mother. They want it ‘back to the way it was.’ Well, that is part of the way it was.”

Atwood was born in Ottawa, but she spent formative stretches of her early years in the wilderness—first in northern Quebec, and then north of Lake Superior. Her father, Carl Atwood, was an entomologist, and, until Atwood was almost out of elementary school, the family passed all but the coldest months in virtually complete isolation at insect-research stations; at one point, they lived in a log cabin that her father had helped construct.

Her mother, also named Margaret—among her intimates, the novelist goes by Peggy—was a dietitian. In the months in the woods, she secured workbooks from school for Atwood and her brother, Harold, who is three years her senior. “The faster you could do them, the sooner you could go out and play, so I became very rapid and superficial in my execution of those sorts of things,” Atwood said. In inclement weather, the children amused themselves by making comic books and by reading. A favorite book was “Grimms’ Fairy Tales,” which Atwood’s parents bought, by mail order, in 1945. “I don’t remember finding any of them frightening,” she wrote later. “By and large, bad things happened only to bad people, which was reassuring; though children have a bloodthirsty sense of justice, they don’t learn mercy until later.”

Her father had grown up poor, in rural Nova Scotia. Her mother, whose family was also from Nova Scotia, grew up in slightly better circumstances: Atwood’s maternal grandfather was a country doctor, and an aunt had been the first woman to get a master’s degree in history from the University of Toronto. Atwood’s parents were resilient and curious and devoted to the outdoors, and the Atwood children were encouraged to be the same. They sledded across a still frozen lake at the start of the season, and canoed across it during the summer months. In Atwood’s second novel, “Surfacing,” a psychological thriller threaded with twisted family relations that was published in 1972, she depicted the landscape of her youth with unsentimental, sensual precision: “The water was covered with lily pads, the globular yellow lilies with their thick center snouts pushing up from among them. . . . When the paddles hit bottom on the way across, gas bubbles from decomposing vegetation rose and burst with a stench of rotten eggs or farts.” When Atwood was about ten, her father built a vacation cabin on an unoccupied island in the lake. The family still retreats there in the summer.

In 1948, Margaret’s father received an appointment at the University of Toronto. (Three years later, another daughter, Ruth, was born.) Margaret, having been raised as her brother’s peer by an unshrinking mother, was unschooled in the conventions of little-girl society. “In the woods, you wore pants not because it was butch but because if you didn’t wear pants and tuck the tops into your socks you would get blackflies up your legs,” she said. “They make little holes in you, into which they inject an anticoagulant. You don’t feel them when they are doing it, and then you take your clothes off and find out you are covered with blood.” In “Cat’s Eye” (1988), Atwood drew on the experience of being transferred from a navigable wilderness to the more treacherous civilization of prepubescent girls. The book’s narrator, Elaine, explains that she has a classmate who “tells me her hair is honey-blond, that her haircut is called a pageboy, that she has to go to the hairdresser’s every two months to get it done. I haven’t known there are such things as pageboys and hairdressers.”

Atwood started writing in earnest in high school. Her parents, who lived through the Depression, were encouraging but practical. She told me, “My mother said, caustically, ‘If you are going to be a writer, you had better learn to spell.’ I said, airily, ‘Others will do that for me.’ And they do.” She followed her brother to the University of Toronto. (A neurophysiologist, Harold Atwood is a professor emeritus in the department of physiology.) Atwood enrolled in the philosophy department, but after discovering that logical positivism was its mainstay, rather than ethics and aesthetics, she switched to literature.

The university’s literature curriculum was unapologetically British: she started with “Beowulf” and took it from there. Canadian literature had yet to be considered worthy of study. A decade later, in 1972, Atwood made a contribution to its establishment as a proper field, with her lucid survey “Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature.” In that book, which made her a household name in Canada, she persuasively posited that, whereas the controlling idea of English literature is the island, and the pervasive symbol of American literature is the frontier, the dominant theme in Canadian literature is survival: “Our stories are likely to be tales not of those who made it but of those who made it back from the awful experience—the North, the snowstorm, the sinking ship—that killed everyone else.”

As an undergraduate, she audited Northrop Frye’s celebrated course on the Bible and literature. Frye helped her secure a fellowship at Harvard, where, in the sixties, she began to write a doctoral thesis on what she called the “English Metaphysical Romance”—the gothic fantasy novels of the nineteenth century. She never finished it. Atwood had embarked on an academic career not for the love of teaching or scholarship but because making a living as a writer seemed an implausible aspiration. “It was thought presumptuous—this is way before the age of creative-writing programs, and writers, to be serious, ought to be dead,” she recalled.

Atwood started her career as a poet. Her first professionally published collection, “The Circle Game,” won the Governor General’s Award in 1966, and has never been out of print. The poems, which take the ring-around-the-rosy children’s game as a starting point for an exploration of male-female relationships, show Atwood’s early aptitude for the unflinching, visceral metaphor. A lover examines the speaker’s face “indifferently / yet with the same taut curiosity / with which you might regard / a suddenly discovered part / of your own body: / a wart perhaps.” Atwood’s first novel, “The Edible Woman,” which was written in 1964 and published five years later, is a contemporary satire in which a young woman, having just become engaged—her husband-to-be is clearly the wrong guy—finds herself unable to eat.

Some reviewers hailed Atwood’s work as a voice of the burgeoning feminist movement. (A reviewer in Time said that the novel had “the kick of a perfume bottle converted into a Molotov cocktail.”) She resisted the identification. “I was not in New York, where all of that kicked off, in 1969,” she said. “I was in Edmonton, Alberta, where there was no feminist movement, and would not be for quite some time.” Atwood was then married to Jim Polk, who had been a classmate at Harvard, and whose teaching job had taken them to the Canadian Northwest. (They divorced in 1973.) “I had people interviewing me who would say, ‘How do you get the housework done?’ I would say, ‘Look under the sofa, then we can talk.’ ”

In the sometimes divisive years of second-wave feminism, Atwood reserved the right to remain nonaligned. “I didn’t want to become a megaphone for any one particular set of beliefs,” she said. “Having gone through that initial phase of feminism when you weren’t supposed to wear frocks and lipstick—I never had any use for that. You should be able to wear them without people saying you are a traitor to your sex.” In a 1976 essay, “On Being a ‘Woman Writer’: Paradoxes and Dilemmas,” Atwood described the mixed feelings experienced by women writers old enough to have forged a writing life before representatives of the women’s movement came along to claim them. “It’s not finally all that comforting to have a phalanx of women . . . come breezing up now to tell them they were right all along,” she wrote. “It’s like being judged innocent after you’ve been hanged: the satisfaction, if any, is grim.”

“Instead of eggs, you’re going to look for lost balls in the water hazards.”

Given that her works are a mainstay of women’s-studies curricula, and that she is clearly committed to women’s rights, Atwood’s resistance to a straightforward association with feminism can come as a surprise. But this wariness reflects her bent toward precision, and a scientific sensibility that was ingrained from childhood: Atwood wants the terms defined before she will state her position. Her feminism assumes women’s rights to be human rights, and is born of having been raised with a presumption of absolute equality between the sexes. “My problem was not that people wanted me to wear frilly pink dresses—it was that I wanted to wear frilly pink dresses, and my mother, being as she was, didn’t see any reason for that,” she said. Atwood’s early years in the forest endowed her with a sense of self-determination, and with a critical distance on codes of femininity—an ability to see those codes as cultural practices worthy of investigation, not as necessary conditions to be accepted unthinkingly. This capacity for quizzical scrutiny underlies much of her fiction: not accepting the world as it is permits Atwood to imagine the world as it might be.

Atwood and Gibson, who met in Toronto publishing circles, spent the seventies living on a farm outside the city. The countryside was cheap, and it provided a congenial environment for Gibson’s two teen-age sons; it also provides the setting for what Atwood acknowledges as some of her most autobiographical writing, in the short-story collection “Moral Disorder” (2006). The title story details the less picturesque aspects of country life. “Susan the cow went away in a truck one day and came back frozen and dismembered,” Atwood writes. “It was like a magic trick—a woman sawed in half on the stage in plain view of all, to reappear fully restored to wholeness, walking down the aisle; except that Susan’s transformation had gone the other way.”

Atwood resists critics’ attempts to find parallels between her life story and her fiction, and has no desire to write a memoir. “I am interested in reading other people’s, if they have had fascinating or gruesome lives, but I don’t think my life has been that fascinating or gruesome,” she said. “The parts of writers’ lives that are interesting are usually the part before they become a well-known writer.” In the mid-eighties, shortly before she started to write “The Handmaid’s Tale” but was already Canada’s most celebrated novelist, a documentary filmmaker named Michael Rubbo spent several days with Atwood and her family at their island retreat in northern Quebec. Rubbo sought to locate the source of Atwood’s inspiration and to uncover the origins of her often gloomy themes, but most of his film is devoted to showing the ways that Atwood politely declined to conform to her inquisitor’s thesis. “I use settings, but that is not to be confused with using real people, and things that have actually happened to those real people,” she tells the filmmaker, while his camera lingers on her hands: she is slicing through the blood-red stalks of rhubarb plants with a chef’s knife and casually discarding the poisonous leaves.

At one point, the Atwoods are given control of the camera, and conduct a strange pantomime in which Atwood sits with a brown paper bag over her head while other family members offer sentence-long characterizations of her. “That woman is my daughter, and she’s incognito,” Atwood’s mother says, in the most illuminating of the remarks. Atwood, after removing the bag, says, “Michael Rubbo’s whole problem is that he thinks of me as mysterious and a problem to be solved. . . . He’s trying to find out why some of my work is sombre in tone, shall we say, and he’s trying for some simple explanation of that in me or in my life, rather than in the society that I am portraying.” At another moment, she suggests that her novels should be thought of as being in the tradition of the Victorian realist or social novel, and should be read in the light of objective facts, rather than subjective experience.

Some of her most perceptive readers have taken this approach. The novelist Francine Prose, reviewing “Alias Grace,” noted that “Atwood has always had much in common with those writers of the last century who were engaged less by the subtle minutiae of human interaction than by the chance to use fiction as a means of exploring and dramatizing ideas.” At its best, Atwood’s fiction summons an intricate social world, whether it be a disquieting vision of the future, as in “The Handmaid’s Tale,” or a vividly rendered past, as in “Alias Grace” or “The Blind Assassin”—a genre-bending tour de force set partly in small-town Canada in the nineteen-twenties, for which Atwood won the Booker Prize, in 2000.

Like her Victorian forebears, Atwood does not shy away from the idea that the novel is a place to explore questions of morality. In an e-mail, she wrote to me, “You can’t use language and avoid moral dimensions, since words are so weighted (lilies that fester vs. weeds, etc.) and all characters have to live somewhere, even if they are rabbits, as in ‘Watership Down,’ and they have to live at some time . . . and they have to make choices.” The challenge, she noted, is avoiding moralism: “How do you ‘engage’ without preaching too much and reducing the characters to mere allegories? A perennial problem. But when the large social issues are very large indeed (‘Doctor Zhivago’), the characters will act within—and be acted upon by—everything that surrounds them.”

At the same time, Atwood’s best fiction is sustained by a specificity of detail—a capacity for noticing—that might be expected from one whose scientist father introduced her to a microscope at a young age. One morning, while we were walking in her neighborhood, Atwood bumped into an old friend, Adrienne Clarkson, a college contemporary who went on to have a distinguished career as a broadcaster, and, for six years, as the governor general of Canada. “We are going to crawl into our eighties together,” Clarkson said, inviting us to her home for tea. The women reminisced about studying with Northrop Frye. “He is the person who talked me into going to grad school instead of moving to Paris, and living in a garret and drinking absinthe,” Atwood said. “But, Adrienne, you did move to Paris.”

“You came to visit,” Clarkson said.

“And you were painting your fingernails a beautiful shade of red,” Atwood continued.

“How frivolous of you to remember that,” Clarkson said, fondly.

“How novelistic of me to remember it,” Atwood said.

Not long ago, a history society at the University of Toronto, which was compiling a video archive of notable alumni, asked to interview Atwood about her college days. On a chilly afternoon in January, she found her way to an upper room in the university’s Gothic Revival student center. Four eager undergraduates, all women, were there to film and quiz her. Atwood sat by a leaded-glass window against a gray sky, and amiably answered questions about what it was like being a young woman on campus in the fifties. “Whatever things are like when you are young, they seem normal, because you have nothing to compare them to,” she said. “For instance, I would not ever have worn jeans to high school. It would not have been permitted except on football days. They wanted us to wear jeans on football day, so we could sit on the hill and not have anyone looking up our skirts. It takes a while to figure this out, but now I realize that must have been the reason.”

In those days, Atwood said, there was no fear of rape on campus, as there seemed to be today. “I am not saying that it didn’t happen, but you would never hear of it,” she said. “And I would suspect that the chances of that happening were quite low, because what everybody was afraid of then was getting pregnant. The boys were afraid of getting pregnant, too, because you could end up married at an early age that way, and people didn’t particularly want that. But there was no Pill.”

One young interviewer, wide-eyed, said, “It is very interesting to consider the importance of the Pill, not just for women but in changing society. I hadn’t really considered it.”

Atwood continued talking about changing mores—the supplanting of the panty girdle by nylon tights, and the consequent innovation of the miniskirt. But when one of the students fumbled with the camera, in an effort to renew its memory card, Atwood took the opportunity to turn the tables.

“I was astonished to see that the Polaroid camera has come back—why? What do you do with a Polaroid picture?” she asked.

The students, delighted, offered a chorus of explanations: such images combined the instant gratification of the selfie with the pleasure of a physical object that could be pinned on a wall. Atwood went on to seek their views on other surprisingly resurgent technologies—vinyl records, even cassette players—and then shifted to something more up-to-date. “Do you know an exercise app called Zombies, Run?” she asked.

“Is that, like, where you go for a run and zombies chase you?” one student asked. Yes, Atwood said: the app, a kind of interactive podcast, plays an apocalyptic story line in a listener’s ears as she jogs, thus making a workout more entertaining, if you like that sort of thing. “I’m in one of the episodes,” Atwood announced. She has a cameo as herself: her voice is supposedly being transmitted over a crackling phone line from Toronto.

“If we carpool, we can all save some money on our midlife crises.”

Finally, the students’ camera was working. Atwood faced it again, and said, brightly, “So, let’s see. What else do you want to know?”

Her openness to younger people is, in part, a consequence of the passage of time: there are many more younger people around than older ones, so she’d better be open to them, if she’s going to be open to anybody. But it is also temperamental. Zombies, Run! was co-created by Naomi Alderman, a British novelist in her early forties, who is also a video-game designer. She and Atwood became friends after Atwood chose to be her mentor, through a program sponsored by Rolex. “She was intrigued that I might know about something she doesn’t know about yet, and I might be able to tell her about it,” Alderman said. “I don’t think she judges anything in advance as being beneath her, or beyond her, or outside her realm of interest.” Alderman has accompanied Atwood and Gibson on several bird-watching vacations, including one earlier this year in the rain forests of Panama. “We stayed in tents,” Alderman told me. “And the first night I was going back to my tent and my headlamp caught these blue shining glints on the jungle floor, and every single one of these glints was a pair of spider’s eyes staring at me. When I told Margaret, she was very disappointed—she really wanted to see the spiders.”

Atwood’s embrace of technological innovation is sometimes more theoretical than practical: she has yet to master streaming video, so she still watches DVDs. Occasionally, her fascination with technological processes, combined with an incomprehension of them, can have productive results. A dozen or so years ago, when videoconferencing technology was still a novelty, Atwood wondered whether it might be possible to develop a means of conducting book signings remotely. “I thought of the writing flying through the air, and materializing somewhere else,” she said. Her flight of fancy, combined with some technical and marketing know-how assembled by Matthew Gibson, her stepson, resulted in the LongPen, a robotic device that enables a writer—or anyone—to sign a paper remotely in a manner that replicates the speed and pressure of the original autograph, and is indistinguishable from it. (Gibson has since created an e-signature company, Syngrafii, and it sells the LongPen, which is marketed less to weary authors than to financial and legal companies.)

Atwood was an early adopter of Twitter, signing up in 2009; she now has about a million and a half followers, though she is aware that some of that number must be bots. “I do sometimes get ‘I miss your dick’—they don’t read the fine print,” she said. She appreciates followers who have a specialized interest in the sciences; they help her keep abreast of recent developments that might be of interest for a future writing project, or resonate with a past one. She engages, often cheerily, with her followers and others, sometimes on topics that another writer might avoid. “Only ‘race’ is the human race, sez me. (And says science.),” she wrote in response to one user’s speculation that she was Jewish. “But no, I wouldn’t have ended up in a Hitler death camp for that reason.”

For years, Atwood has argued that Twitter in particular and the Internet in general have been good for literacy. “People have to actually be able to read and write to use the Internet, so it’s a great literacy driver, if kids are given the tools and the incentive to learn the skills that allow them to access it,” she said, while being interviewed at a digital-media conference in 2011. She has been a champion of Wattpad, a story-sharing site founded in Toronto a decade ago. In her view, it not only provides a place for North American teen-agers to publish their own zombie tales; it also offers cell-phone-equipped readers in the developing world with an entry point into fiction, even if they have no access to libraries, schools, or books. Her 2015 novel, “The Heart Goes Last,” which takes the premise of for-profit prisons to monstrous, comic ends, was excerpted on Wattpad. Atwood has also published a collection of poems, “Thriller Suite,” serially, on Wattpad; the book has been viewed more than three hundred and eighty thousand times since then, presumably reaching many readers who had never bought a volume of poetry.

She believes that early fears, among some observers, that the advent of the Web would mean the end of books were misplaced. “I think we know now that, neurologically, there are reasons why that isn’t going to happen,” Atwood said. “Installments on a phone—those, the brain can handle. ‘War and Peace,’ maybe not. Though ‘War and Peace’ was first published in installments, by the way.” She is fond of saying that, with all technology, there is a good side, a bad side, and a stupid side that you weren’t expecting. “Look at an axe—you can cut a tree down with it, and you can murder your neighbor with it,” she said. “And the stupid side you hadn’t considered is that you can accidentally cut your foot off with it.”

A few years ago, Atwood became the first author to participate in a conceptual art project, the Future Library, which was conceived by a Scottish artist named Katie Paterson. In the course of a hundred years, a hundred writers will contribute a manuscript to the project. The manuscripts will remain unread except for their titles—Atwood’s is “Scribbler Moon”—until 2114, when they will be printed on paper made from a thousand pine trees that have been planted in the Nordmarka, a forest not far from where the library will be maintained, in Oslo, Norway.

“Being the kind of child who buried things in the back yard in jars, hoping that someone else would dig them up sometime, I of course liked this project,” she told me. Atwood has a keen interest in conservation: she uses her Twitter feed to highlight ecological issues ranging from the decimation of the bee population to ocean pollution. The optimism inherent in the Future Library—the belief that there will be readers, and a world for them to inhabit—seems at odds with some of the darker scenarios in Atwood’s fiction, and I suggested as much to her.

“This is not a question of expect,” she said. “It is a question of hope. It is a question of faith rather than knowledge. You wouldn’t do it unless you thought there was a chance.” Humans, she said, “have hope built in,” adding, “If our ancestors had not had that component, they would not have bothered getting up in the morning. You are always going to have hope that today there will be a giraffe, where yesterday there wasn’t one.” At the same time, Atwood loves to entertain notions of how degraded our future might become, and what effect that might have on the human race. She speculates that, if our atmosphere becomes too carbon-heavy, with a dwindling in the oxygen supply, one of the first things that will happen is that we will become a lot less intelligent.

But a novelist necessarily imagines the fate of individuals; the human condition is what the novel was made for exploring. “We just actually can’t bear the idea of nothing,” Atwood said. “I think that is partly to do with grammar. You say, ‘I will be dead,’ but there is still an ‘I.’ There is still a subject.” Her novels, she went on, are not without hope, either. “The Handmaid’s Tale” has a coda, in the form of an address given, in 2195, by a keynote speaker at an academic conference, the Twelfth Symposium on Gileadean Studies. Civilization has survived, even to the point of sustaining groaningly bad academic puns. (Women fleeing Gilead, a professor notes, cross the border via “The Underground Frailroad.”) “I have never done everybody in,” Atwood said. “I have never polished them all off so that there’s nobody left alive, now, have I? No.”

In the early aughts, she began an ambitious cycle of novels exploring a different kind of dystopian future. The Maddaddam Trilogy—“Oryx and Crake,” “The Year of the Flood,” and “Maddaddam”—was published between 2003 and 2013. The books depict a North American landscape that is ravaged by ecological disaster and inhabited by a genetically modified race of quasi-humans, the Crakers. As usual, Atwood researched her subject voraciously, and this time she was further enabled by the Internet. The trilogy crackles with a gleeful inventiveness that is sometimes tonally at odds with its apocalyptic content: the Crakers’ skin cells have been modified to repel ultraviolet rays and mosquitoes, for example, and the capacity for sexual jealousy has been edited out of their genome.

“Vinnie, we gotta talk about what ‘bookmaking’ means.”

One evening in Toronto, Atwood invited me to her home, where we sat in its spacious kitchen on tall stools at a counter, overlooking her wintry, barren-looking garden. Graeme Gibson poured three glasses of whiskey while Atwood sorted through Christmas cards, dispensing with the chore as efficiently as if she were slicing rhubarb. I remarked on an aspect of “Oryx and Crake” that had moved me. The protagonist, Snowman, apparently left alone in the world, strives to remember unusual words he once knew. Atwood writes, “Valance. Norn. Serendipity. Pibroch. Lubricious. When they’ve gone out of his head, these words, they’ll be gone, everywhere, forever. As if they had never been.” Reading this passage in recent months led me to think about the catastrophic devaluation of intellection that seems to have occurred in American society: the willful repudiation of rigorous thinking, and objective facts, that helped propel Trump to victory. I remarked to Atwood that it felt like a prescient metaphor.

“It feels like real life,” Atwood replied, quickly. “I am sure every generation feels that way, as they see younger people coming up who don’t know what they are talking about.” She asked if I knew Edith Wharton’s short story “After Holbein”: “This old gentleman in New York society goes off to visit this hostess of his youth, and they sit at this enormous table, and everything is as wonderful as he remembers it, and there are bouquets of flowers, and this delicious food, and they have this wonderful conversation and she looks as beautiful as ever. And you see it all from the point of view of the servants, and it’s two old people sitting at a table eating gruel, and the flowers are all bunches of newspaper.”

News comes often to Atwood of friends who have died, or are ailing. Gibson has been given a diagnosis of early dementia, and they are both supporters of the Canadian dying-with-dignity movement. “The story of Wharton’s that really terrifies me is ‘The Pelican,’ ” she went on, recalling a tale in which a well-born widow takes to giving public lectures to support her young son, and then continues to give them for decades, even after the son is a grown man. “People are very sympathetic, but the lecture itself is like watching someone unreeling from her mouth a very long spool of blank paper,” Atwood said. “That’s the metaphor that frightens me—that I am going to be up in public, unravelling from my mouth a long spool of blank paper.”

In March, Atwood came to New York City, for the annual National Book Critics Circle award ceremony, where she was being given a lifetime-achievement award. (Atwood recently remarked, on an Ask Me Anything thread on Reddit, that she is at the “Gold Watch and Goodbye” phase of her career.) The ceremony was held at the New School, and the collective mood of the assembled editors, critics, and writers—a concentration of New York’s liberal intelligentsia in its purest form—was celebratory, as such events always are, but also agitated and galvanized. That morning, President Trump had issued his first federal budget plan, and he had proposed eliminating the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, as well as ending funding for public broadcasting, and closing agencies devoted to social welfare and environmental oversight. The crowd felt like bruised defenders of a civilization that they hadn’t realized was susceptible to attack.

Trump’s agenda was criticized by many of the award recipients. Michelle Dean, a young Canadian writer who won the association’s annual prize for excellence in reviewing, declared, “The struggle we presently find ourselves in is not a mistake, and not a fluke. . . . It crept into our lives while we were napping. Power sometimes works that way, but I still wish we hadn’t missed it.” Lately, Dean added, she’d been rereading “The Handmaid’s Tale” for the first time since high school: “There are so few books like that being published right now. The application of literary intelligence to this question of power—it’s kind of out of style. And many writers just seem more interested in exploring the self.”

Two days before Trump’s Inauguration, Atwood had published an essay in The Nation, in which she questioned the generalities sometimes made by left-leaning intellectuals about the role of the artist in public life. “Artists are always being lectured on their moral duty, a fate other professionals—dentists, for example—generally avoid,” she observed. “There’s nothing inherently sacred about films and pictures and writers and books. ‘Mein Kampf’ was a book.” In fact, she said, writers and other artists are particularly prone to capitulating to authoritarian pressure; the isolation inherent in the craft makes them psychologically vulnerable. “The pen is mightier than the sword, but only in retrospect,” she wrote. “At the time of combat, those with the swords generally win.”

At the New School, when Atwood, wearing a long black dress with a patterned black shawl draped around her shoulders, was summoned to the stage, she took a cheekier tack than she had taken in the Nation essay. “I’m very, very, very happy to be here, because they let me across the border,” she said, her voice low and deliberate. Atwood characterized literary criticism as a thankless task. “Authors are sensitive beings,” she observed, to titters of amusement. “You, therefore, know that all positive adjectives applied to them will be forgotten, yet anything even faintly smacking of imperfection in their work will rankle until the end of time.” An author whom she had reviewed once berated her use of the adjective “accomplished,” she recalled. “ ‘Don’t you know that “accomplished” is an insult?’ ” she deadpanned. “I didn’t know.”

Then her remarks took an exhortatory turn. “Why do I do such a painful task?” she said. “For the same reason I give blood. We must all do our part, because if nobody contributes to this worthy enterprise then there won’t be any, just when it’s most needed.” Now is one of those times, she warned: “Never has American democracy felt so challenged.” The necessary conditions for dictatorship, Atwood noted, include the shutting down of independent media, which mutes the expression of contrary or subversive opinions; writers form part of the fragile barrier standing between authoritarian control and open democracy. “There are still places on this planet where to be caught reading you, or even me, would incur a severe penalty,” Atwood said. “I hope there will soon be fewer such places.” Her voice dropped to a stage whisper: “I am not holding my breath.”

In the meantime, she thanked the book critics, though even her gratitude carried a note of subversion. “I will cherish this lifetime-achievement award from you, though, like all sublunar blessings, it is a mixed one,” she said. “Why do I only get one lifetime? Where did this lifetime go?” ♦

An earlier version of this article misstated the city in Texas where “The Handmaid’s Tale” was banned. It also mistakenly cited the date of first publication in the U.S., rather than in Canada.

Sourse: newyorker.com