When Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America: Millennium Approaches” opened on Broadway, in 1993, in a production directed by George C. Wolfe, the play ended with a winged angel crashing into a dying man’s bedroom from above, shattering lath and plaster. Subsequent directors, including Mike Nichols, who filmed “Angels” for HBO, have also hewed closely to Kushner’s stage directions, which call for unearthly lighting, “a terrifying crash as something immense strikes earth,” and an Angel who floats.

Van Hove once wrote plays, but discovered that he “could make much more personal work through the filter of a text by Shakespeare.”Photograph by Nadav Kander for The New Yorker

In a radically stripped-down interpretation by the Belgian director Ivo van Hove, which was first staged in Amsterdam in 2008, none of that happens. Van Hove’s Angel is a wingless male nurse in white hospital scrubs. There is no ceiling, no bed. The Angel quietly approaches as Prior Walter, who is suffering from AIDS, writhes on the stage floor. The grand words of annunciation with which Kushner’s play culminates—“Greetings Prophet; / The Great Work begins: / The Messenger has arrived”—are delivered by the Angel with conversational mildness.

Van Hove, who is the general manager of the Toneelgroep Amsterdam, the city’s principal theatre, often uses few props and employs minimal sets. In “Angels,” the stage is bare except for a record player and the occasional I.V. pole. When collaborating with his perennial set designer, Jan Versweyveld, who is also his partner of thirty-five years, van Hove establishes mood with music, video, and lighting, and uses actors’ bodies to convey the emotional core of a work. “Angels” takes place in 1985, at the height of the AIDS crisis, but as enacted by the Toneelgroep Amsterdam the play is not about the ravages of an epidemic. “Ivo said that the sickness was a metaphor for change,” Eelco Smits, the actor who played Prior Walter, told me recently. Unlike Stephen Spinella, who played the role on Broadway, and who was so emaciated that audiences gasped when he disrobed, Smits’s Prior did not look unhealthy. “It wasn’t about showing people who were sick but about showing people who are in a transition phase,” Smits said.

Van Hove initially directed the Angel and Prior to sit together and listen to music. But this went too far in downplaying the encounter. The day before opening night, he told the actor playing the Angel to pull Smits up by the hands and spin with him around the stage, like children at the playground, and then release him violently to the floor. Smits objected. “I said, ‘I think I need protection for my knees,’ and Ivo was just, ‘No—go, go, go, do it,’ ” Smits told me. “I got angry with him. We didn’t have time to rehearse it, and I thought, This is stupid.”

But the result is stunning. Over a swelling soundtrack of David Bowie singing “The Motel,” the Angel spins Prior and hurls him down over and over again. Audience members who have lost friends or lovers to AIDS sometimes approach Smits afterward in tears. “One man told me, ‘That throwing around—that is what that disease is,’ ” Smits recalled. “Somehow Ivo knew what there was, in the utter simplicity of that movement. He was thinking more about stuff like that—of using abstract movements of the body—more than making up your face to look gaunt.”

Kushner first saw van Hove’s rendering of “Angels” in 2009, and wept at the scene. “It was shattering,” he told me. “By the sixth time you watch this guy get thrown and land on his butt, your butt starts to hurt. The playfulness of it made the cruelty of it so much more sharp and disturbing: you are dying, with this very silly, undignified thing going on. It made the audience work hard to recuperate dignity from the moment, and cherish it all the more.”

Van Hove said, “I felt very strongly that the appearance of the Angel happens in the mind of Prior. I made it so that everything happens also in the audience’s mind. So we see the Angel just as a nurse. And then the Angel overthrows Prior’s whole life within this moment of swinging him around. I tried to bring out his inner world—of losing his friend that he was in love with, of being alone with AIDS. That is the feeling I tried to express by having him beaten up by this Angel.”

Kushner says that one of van Hove’s gifts is to “make the audience confront the failure to create completely convincing illusions—and the power of the theatre is that failure to create convincing illusions. It is the creation of a double consciousness. Ivo’s impulse is to take that very seriously, and to ask the audience to collaborate in making this thing real.”

Van Hove’s “Angels” played at Bam last year for three nights. (“I could have run it for weeks,” Joe Melillo, bam’s artistic director, says.) This fall, far greater numbers of American theatregoers will have a chance to see van Hove’s work. In November, he makes his Broadway début, with Arthur Miller’s “A View from the Bridge,” which he staged at the Young Vic, in London, last year. “Lazarus,” a new musical work by David Bowie and the Irish playwright Enda Walsh, opens in December at New York Theatre Workshop, which has collaborated with van Hove since the nineties. Van Hove will also be directing a new Broadway production of Miller’s “The Crucible,” starring Ben Whishaw, in early 2016.

“A View from the Bridge” was nominated for seven Olivier Awards, the British equivalent of the Tonys, after it transferred to the West End; it won three, including the award for best director. Like “Angels,” it offers the spectacle of radical condensation: with the actors barefoot on a stage devoid of props, the domestic activities of the Carbone family unfold inexorably, as in a Greek tragedy. The production has a disquieting erotic intimacy and the hurtling pace of a thriller’s climax. Van Hove does not always rely on spareness to make a familiar play seem new. In a controversial production of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” at New York Theatre Workshop in 1998, a claw-footed bathtub dominated the stage. The characters talked around the tub, fought around it, bathed in it, and—in a moment of theatrical wizardry—dived into it fully clothed.

Earlier this year, I went to see van Hove at work with members of the Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s ensemble. They were rehearsing “Kings of War,” an epic production in which five of Shakespeare’s English histories—“Henry V,” “Henry VI,” Parts 1, 2, and 3, and “Richard III”—are condensed into one four-and-a-half-hour-long drama. This was van Hove’s second Shakespearean distillation: several years ago, he and Versweyveld created “Roman Tragedies,” which combined “Coriolanus,” “Julius Caesar,” and “Antony and Cleopatra.” Set in an environment suggesting the war room of a contemporary political campaign, “Roman Tragedies” incorporated live and recorded video. Large screens showed footage from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan or closeups of actors’ faces while a digital ticker above the stage broadcast headlines from CNN. Between acts, audience members were invited to go onstage—where they could perch on the couches, sit on the floor, or visit a bar that had been set up toward the back—and then remain there when the play resumed. This had the startling effect of transforming the audience into the Roman populace, whose moods and whims the actors were manipulating.

Whereas “Roman Tragedies” explored the dynamic between politicians and the public, “Kings of War” highlights the demands of power on an individual. The set evoked Churchill’s wartime bunker in Whitehall: beige walls, old maps, a narrow cot with a military-issue blanket. Behind the room was a hidden structure of interconnected corridors, painted white and brilliantly lit. Much of the action of the play is conducted there, captured by a roving cameraman and projected onto a screen above the bunker. In the corridors, Henry V covetously fondles the crown of his not quite dead father, and Richard III approaches Henry VI, preparing to strangle him. “They are like corridors in a big palace, or in the White House, or wherever people are negotiating and making decisions,” van Hove explained at the rehearsal, which took place in a studio on the outskirts of Amsterdam. “What happens in the corridors is something you shouldn’t say in the public world, in open life.”

Van Hove, who is fifty-six, is soft-spoken and precise. Slim and upright, he has an air of imperturbable self-possession that is occasionally softened by a display of humor. He exudes discipline. In “Kings of War,” he explained, “a leader has to decide on the most extreme thing—to go to war or not.” He continued, “That is, for a president or a king, the most difficult decision to make. Because you can win a war, and then you are a hero, but even then there may be a lot of casualties. Even when you win a war, in the people’s mind you can have lost it.”

Earlier in the season, the company had presented a production of Friedrich Schiller’s “Mary Stuart” and a new play adapted from Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead.” “Ivo is very interested in leadership,” Versweyveld, who was at the rehearsal, told me. Versweyveld, who is fifty-seven, is compact, with a shaved head; that afternoon, he had been taking photographs of the actors as they rehearsed. He said of van Hove, “He reads about other leaders, and he is always trying to make himself a better leader, and so this of course is at the center of his existence.”

“You’re not bending your knees.”

In rehearsal, van Hove usually works steadily through the text, reaching the end of the play just before the first public performance. There are occasional deviations from this practice. Thomas Jay Ryan, who played Philinte in van Hove’s version of “The Misanthrope,” at New York Theatre Workshop, said, “I had a very big speech he would never let me do in rehearsal. We would get right up to the speech and he would say, ‘You are not ready yet.’ ” By the time van Hove was willing to rehearse it, Ryan said, “I had all this emotion that came naturally.” He went on, “It had this other layer and life. I was shouting and throwing things. I would never have been able to do it a week earlier. Afterward, Ivo said, ‘I’m sorry, Tom. That is the way you are going to have to do it.’ ”

Van Hove hates auditions: he makes decisions quickly, and resents the time lost to politesse. When working with his permanent company, he casts by fiat, assigning actors to play characters who, among other things, may have to fight each other or have sex with each other—both fairly frequent occurrences in van Hove productions. “Because he knows everyone very well, sometimes he likes to make explosive combinations—like a kid who lets insects fight,” Eelco Smits told me. “Sometimes the chemistry between actors is really sexual, and he uses it.” Actors are expected to be “off book”—know all their lines—from the first day of rehearsal, a practice that Americans often find disconcerting. Van Hove likes to rehearse only five hours a day. Juliette Binoche, who is currently starring in a touring production of van Hove’s “Antigone,” which was at BAM this fall, told me, “It has to print inside you very quickly. You don’t go back often. It is very raw. In a way, it is very frightening.”

A van Hove rehearsal often begins after many months of forensic preparation. Chris Nietvelt, a Belgian actress and a member of the Toneelgroep Amsterdam, who has worked with van Hove for more than thirty years, told me, “He has one piece of paper—‘That is what the play is about. That is why I want to do it.’ ” When I was in Amsterdam, the première of “Kings of War” was just over three weeks away, and van Hove was still only on “Henry V,” rehearsing the prelude to the Battle of Agincourt with Ramsey Nasr, a Dutch-Palestinian actor who had been cast as Henry V. Van Hove described the monarch as “a good leader who listens to his advisers, who puts forward again and again the right questions.”

Nasr is an actor of intense intelligence; he is also a writer and a former poet laureate of the Netherlands. He knelt by the bed, in a contemporary officer’s uniform, as he delivered Henry’s prayer for his men before battle. At the scene’s end, van Hove joined Nasr onstage, speaking intently to him in a low voice. Van Hove modulates his directives to match the actor’s temperament. “Ramsey is a control freak,” van Hove told me later. “If something on the table is here, and tomorrow it is over there, he would be, like, ‘But yesterday this was here.’ So I know I have to deal with that, because then he feels good. If I were to say, ‘Ramsey, I don’t mind where it is,’ that would be disturbing to him.”

In preparing “Kings of War,” van Hove gave particular attention to a soliloquy in “Henry VI, Part 3,” in which the monarch, preparing to lead his troops, wishes instead for the simple life of a shepherd. (“How lovely! / Gives not the hawthorn-bush a sweeter shade / To shepherds looking on their silly sheep.”) Van Hove, along with Versweyveld and Tal Yarden, their long-standing video collaborator, had decided to dramatize Henry’s failure to shoulder his kingly burden by bringing his fantasy to life. On the overhead screen, a flock of real sheep would suddenly materialize within the white corridors of power, as if from Henry’s imagination.

It was not the first time that van Hove had included animals in a production: his Macbeth rode a cart horse into battle; a memorable version of O’Neill’s “Desire Under the Elms” featured eight cows onstage. That evening, after Nasr and the other actors in “Henry V” had left, van Hove and the production team stayed on. Outside the rehearsal space, a truck pulled up, from which bleats emanated. Several animal wranglers laid black vinyl matting on the floor of the bunker. When forty-odd sheep came skittering down the gangplank into a temporary enclosure, the production team gathered around, everyone exclaiming with delight. Van Hove walked the other way. “I hate animals,” he muttered.

The sheep were herded stage left, into the white corridor. Smits, who was playing Henry VI, entered the corridor stage right and, followed by a cameraman, approached the flock. But, instead of gathering around him, the sheep fled in the opposite direction, bumbling into each other and defecating indiscriminately on the white floor. The crew cast anxious glances at van Hove and Versweyveld. Someone asked if the shit could be cleaned up in postproduction.

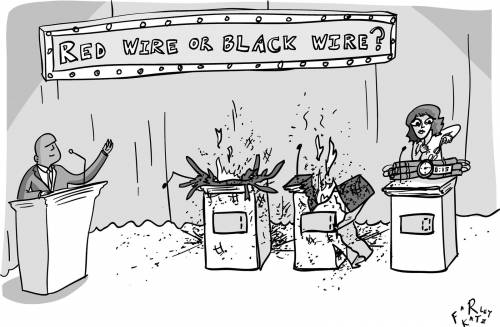

“Whoa—you’re gonna need a whole new string!”

Van Hove, looking irritated with the proceedings, gave curt instructions to the cameraman, who was supposed to keep the shot low, filming only Smits’s legs and back, so that other actors could eventually take on the role; but the camera kept capturing the back of Smits’s head, or his face. Exasperated, van Hove repeated his intentions. Smits persevered with the sheep, whose greasy wool was staining the walls of the corridor. He picked up a lamb in his arms. Finally, the sheep ran toward the camera. “This is what we need,” van Hove exclaimed. “This is the enthusiasm I need.”

After an hour, the sheep were herded back into the truck, and a crew member appeared with a bushel of brooms and mops. Van Hove drove back to the center of Amsterdam, where he and Versweyveld live in an impeccably ordered apartment overlooking a canal. Van Hove coughed. “It’s these fucking sheep,” he said. “I don’t really hate animals. I just cannot communicate with them, really.”

Van Hove grew up in rural Belgium, amid farmers and coal miners. His father was the pharmacist in the village where the family lived, which had a population of two thousand. “In such a small community, that is considered as being of the higher class,” van Hove told me one afternoon over coffee at Café Stanislavski, in the lobby of his theatre, which is on a busy square crisscrossed by clanging trams and insouciant cyclists. “The doctor came to our house, and the architect, and sometimes the mayor, and the priest, and they drank Cognac every morning at eleven o’clock. I remember that happening every day—though of course it’s not true.” Van Hove says that he felt like an outsider among his working-class schoolmates, and told himself, “I have to go from here. This is not my place.”

At eleven, he went to boarding school. “For the first three weeks, I wept,” he said. “Then it became the best time of my life.” Van Hove discovered theatre there. “On Wednesday afternoons, there was no class, so you could do sports, or you could go to the city to meet girls, or you could join the theatre company,” he said. “We would work on a play that we would present at the end of the year. It felt like the boarding school was a walled world within the world, and the theatre was another walled world within it. That felt so warm, so good.” He went on, “I learned there the awareness that, once you close that rehearsal-room door, everything is allowed—I can express every fantasy and obsession. It is total freedom of your mind, of your life.”

At boarding school, he realized that he was gay. It was the early seventies, and homosexuality was not openly discussed. “But boarding school is a perfect place, of course,” he said. He fell in love with a classmate who later died in a bicycle accident. “I have the feeling that I lived my life once through already, in boarding school. That I experienced everything—deep unhappiness, deep mourning,” he told me. When one of van Hove’s teachers taught a class about the atomic bomb, he did so not by showing pictures of atrocities but by explaining how an atomic bomb worked. “I didn’t sleep for three nights,” van Hove said. “In my fantasy, I could imagine it.” From this, he learned that “you don’t have to show everything in a graphic way.”

He went to law school, at his parents’ insistence. “But I am glad I studied law, because in Belgium, for the first two years, you do philosophy, you do psychology,” he told me. “I studied American law, with all these precedents—and I loved that, finding your way into a system. But, in the third year, at a certain moment I looked up and thought, I am in a library. I was in a library yesterday. I will be in a library tomorrow. And I will be in a library in ten years’ time, in twenty years’ time. I stopped that day.” His parents were dismayed by this decision, and by his coming out. “They didn’t know how to cope with it, and I didn’t discuss it with them,” van Hove said. “I think they are allowed to feel how they feel—I cannot make them feel something that they don’t feel. And so I kept my distance.”

He transferred to an arts school, in Antwerp, where he began to study directing. Soon thereafter, he met Versweyveld, an aspiring artist, at a modern-dance workshop in the city. “We started as a couple, but it was immediately clear that to survive as a couple we had to do something together,” van Hove told me. “Two young men of twenty—it’s a lot of testosterone going on. And two people who are ambitious in a deep way—not ‘I want to be’ but ‘I want to do something in life.’ ” The partnership has been remarkably durable and productive. Van Hove has never made a play without Versweyveld, and administrators and actors with whom they work testify to the inextricability of their talents in producing the final result. “We never broke up,” van Hove told me. “That is amazing—as a homosexual, in that time, working in the theatre. I think we did well.”

“I hoped your father had missed the latest men’s-fashion supplement in the New York ‘Times,’ but—alas—he did not.”

While studying in Antwerp, van Hove was reading the work of such theatre theorists as Antonin Artaud. “He talks much about the hidden things in human beings, and says that the theatre is about bringing out these darker sides of us,” van Hove said. He and Versweyveld were also inspired by new work coming out of the United States; among other things, they saw the Wooster Group perform “Point Judith,” a theatre piece based on “Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” at a festival in Brussels in 1981. “There was video, there was dancing—it was a totally new attitude toward theatre,” van Hove said. At the time, Belgian theatre was very conventional, and the route to success was to apply for government subsidies. “There was a new generation who were dissatisfied, and they started to make their own theatre,” Johan Thielemans, a professor of theatre history at the Royal Conservatoire of Antwerp, said. “They didn’t work in established theatres. They thought they had to work in the margins.”

Van Hove and Versweyveld opened a brasserie in Antwerp to fund theatre projects. Their first production, in 1981, titled “Rumors,” was somewhere between a play and performance art, and was staged in a deserted laundry facility. Written by van Hove, it featured a young man named Matthias, who is possibly schizophrenic, and who must navigate among doctors, controlling women, and punk teen-agers. The production came to the notice of David Willinger, who teaches theatre at City College, in New York. “I didn’t know Flemish, but it didn’t matter—I walked out saying, ‘This is one of the best things I’ve ever seen,’ ” Willinger told me. “It was totally original, and had a level of abstraction I would not have expected. It used all the levels in this warehouse, and Jan’s lighting was like a character in the play.’ ”

“Rumors” was based, in part, on a drama in van Hove’s own family: his brother, two years younger, had been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia in his late teens. As children, van Hove and his brother were very close—“I bullied him, he bullied me, you know”—but they had grown apart. “His illness happened at the same time as my detachment from our parents was happening,” van Hove told me. “I regret that I couldn’t be there for him much more. I was selfish, probably. But I was developing my own life more, in quite difficult circumstances, and I couldn’t help my parents deal with it.” As a young man, van Hove was “more arrogant and cold and driven,” Willinger says. “I think he wanted to accomplish something really hard in life, and he sensed all the resistance—bureaucratic, environmental. I think he was wearing blinders. He would allow in only what was going to serve him. I imagine the young Brecht was like that, too.”

Van Hove began to adapt and direct the work of other, usually long-dead writers. “I discovered I could make much more personal work through the filter of a text by Shakespeare that was four hundred years old—that it was much more directly about me, and about my life,” he told me. “My productions are my massed autobiography: if you look at all the plays I’ve done since I was twenty, you know who I am.” In 1987, he staged Euripides’ “The Bacchae.” “The performance started with the prologue, and Dionysius completely nude,” Pol Arias, a Dutch critic, recalls. “Later, we saw him in pumps, wearing a small transparent cloth, with little wings on the back of his head—a very ambiguous character, neither good nor bad.” At intermission, Arias was approached by a couple he’d never met—van Hove’s parents. “His mother told me, ‘Let us say we are quite a bit more conservative than what our son is doing in theatre.’ I answered that there was no need to be ashamed—that they could be proud of what their son was doing, because he was a little genius.”

More recently, he and Versweyveld have staged versions of movies, with adaptations of films by Antonioni, Bergman, and Cassavetes. “When you get to do a movie script onstage, it is like a world première,” van Hove told me. “It is like you get to be the first director to do ‘Hamlet.’ You have to invent a theatrical world for the first time.”

For Ingmar Bergman’s “Cries and Whispers,” which van Hove directed in 2009, he set himself the challenge of representing death onstage in an honest way. “Death is always nothing in theatre—it is very difficult to do,” he said. His father had recently died, and his memories of that experience guided his vision of the central character, Agnes, who is an artist succumbing to cancer. As Agnes, Chris Nietvelt flung herself around the stage, smearing her body with Yves Klein-blue paint. Lying lifeless, she was stripped naked and washed by her maid. “I had her die twice—once the way you want to die, like my father died, with people all around him, caring for him,” van Hove said. “And then there is the other moment of the horrific death struggle—alone. The way I am afraid it will be.” Nietvelt said of van Hove’s methods, “We go very far, physically, mentally. But that is the way we want to make theatre. It is what we call, in Dutch, waarachtig. It means something that’s not true but feels so true that you believe it. And that truthfulness can also be conveyed by your body.” Nietvelt added, “I never fall on my knees in normal life. I fell on my knees, I think, five hundred times for Ivo.”

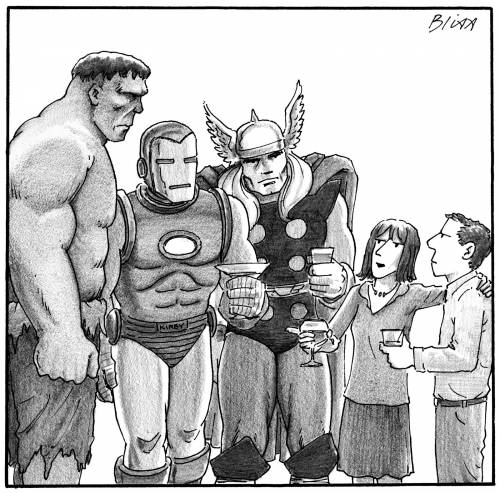

“Incredible Hulk, Invincible Iron Man, Mighty Thor, meet Unremarkable Ed.”

In the mid-nineties, his productions came to the attention of Jim Nicola, of New York Theatre Workshop. Nicola began inviting him to remount his productions of works by O’Neill, Williams, and other American playwrights, but with American actors instead of Dutch ones. The young American director Sam Gold says, “It was seeing American plays filtered through a director whose vision wasn’t mired in the conventions of contemporary American revivals—a director who wasn’t married to the text, and was trying to tell the story about how the plays related to him and his consciousness.” Gold, who won a Tony this year for “Fun Home,” is a guest director at the Toneelgroep Amsterdam this season, working on a new, Dutch-language production of “The Glass Menagerie.”

In New York, van Hove established almost an alternate company: a coterie of familiar actors, many of whom he has now been working with for years. “He never asks me to do what I can do—he leads me to do things I didn’t know I could do,” the actress Elizabeth Marvel told me. In his 2010 production of “The Little Foxes,” at New York Theatre Workshop, Marvel was directed to play Regina as someone whose anger at her relatives was so intense that she seemed on the verge of losing all self-control. “We were surfing this crazy Jungian tidal wave,” she said. “It was hypersexual. I would literally climb the wall, and hump the wall. It is hard to explain. It is a dream state that is more real than reality that I sometimes find myself in, that Ivo helps create.” When the show ended, Marvel said, it was disorienting to work again with more conventional directors: “I remember Neil Armstrong talking about what it was like when he returned from space, how it took him a very long time to reassimilate. The earth was not what he knew it to be anymore—he knew there was this whole other realm. That is very similar to my experience with Ivo.”

In 2005, Hans Kesting, who has played many important roles in van Hove’s productions, played Petruchio in “The Taming of the Shrew.” In a scene in which the title character, Katherina, was meant to be enraged, the actress playing her, Halina Reijn, stood on a table, screaming. “In rehearsal, we were pushing to the limits,” Kesting told me. “And Ivo said, ‘Something should happen that she can’t hold it in anymore. Her anger is not sufficient anymore, screaming is not sufficient, she is so frustrated now. What should she do now?’ ” Jan Versweyveld supplied an answer: “She should pee on the table.” Kesting told me, “It was water, of course—we had to find some sort of contraption to put on her.” In an added degree of boundary crossing, Kesting licked up the urine. The staging wasn’t merely shocking, Kesting said, for it wittily captured the delirious one-upmanship of Katherina and Petruchio. “In the show, it was always such a strong moment,” he said.

Physical injuries are not uncommon among van Hove’s actors. Joan MacIntosh still sees a chiropractor for a neck injury that was exacerbated by the demands of playing Alice James in Susan Sontag’s “Alice in Bed.” She spent the whole play in a specially constructed chaise longue that was molded to her body but off-kilter, so that her pelvis was permanently cocked at an odd angle. It was palpably clear to the audience that Alice, though reclining, was not relaxed. MacIntosh has no complaints: “I would do anything Ivo asked me to do that was humanly possible onstage.”

Van Hove does not choreograph his fights. In “Scenes from a Marriage,” an adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s TV miniseries, which he directed in New York last year, three pairs of actors—each representing the same married couple—engaged in fifteen-minute brawls. Alex Hurt, one of the actors playing the husband, Johan, told me, “It was one of the most unsafe, and particularly fantastic, things I have ever done in a play. Ivo just said, ‘Now you kill her—kill her with your words.’ So we’d all be veining at the neck, screaming our heads off, going at it. And then he would go up to the wives and say, ‘Kill him. Now you kill him.’ ”

“I can no longer tell the difference between what’s real football and what’s fantasy football.”

With Versweyveld and Tal Yarden, the videographer, van Hove often attempts to subvert received wisdom about famous works, sometimes to very controversial effect. He directed a Dutch-language production of “Rent,” in 2000. In the original production, which ran on Broadway for twelve years, the character of Mimi almost dies but is miraculously resurrected. In van Hove’s pitiless version, Mimi dies, with her last moments represented on video. Van Hove’s iconoclasm is, in part, a function of his position as a native speaker of Flemish working principally in Dutch, which has relatively few speakers and a limited literary canon. Just as, when working in English, van Hove feels no duty to Elia Kazan in his interpretation of the works of Tennessee Williams, he does not feel bound to the text of an English-language masterpiece when he is using a Dutch translation. There is inevitably a poetic diminishment when Shakespeare is rendered in a language other than English, but there can also be a recovery of a play’s elemental drama. Van Hove’s “Roman Tragedies” eliminates the first scene of “Antony and Cleopatra,” which includes a voluptuous embrace and depicts “the triple pillar of the world / transform’d into a strumpet’s fool.” But this elided verse is later enacted, during Antony’s passionate leave-taking of Cleopatra before battle. As Antony dresses, the couple laugh and fumble cupidinously; they kiss passionately for a full minute as the music—Bob Dylan singing “Not Dark Yet”—surrounds them, and Antony’s advisers look sternly on. Joe Melillo, of BAM, said of the production, “People couldn’t talk at the end—the death of Cleopatra was so emotional that people were sobbing.” Van Hove’s “Kings of War,” which had its première in Vienna in June, eliminated the buildup to the War of the Roses—a cut that an English director would probably have found harder to make. What remained was “like watching a great cable miniseries,” Sam Gold said. “It has this populist thing—this page-turning energy. You feel like you are watching Netflix, and when you get to the end of ‘Henry V’ you just hit ‘Next Episode.’ ”

When David Lan, the artistic director of the Young Vic, first suggested to van Hove that he might direct “A View from the Bridge,” he resisted. As Versweyveld recalls it, van Hove said, “It’s a well-made play. I hate it. There is little room for any roller-coaster ride.” Lan had wanted to work with van Hove after seeing “Roman Tragedies.” “I like theatre that is as complicated and as intellectually and emotionally contradictory and complex and challenging as my life,” Lan told me. “ ‘Roman Tragedies’ was like that—the ludicrous ambition of it, and the craziness of it. It’s a cliché to say you want art to change you, but I didn’t know you could experience things onstage in that way.”

For the Young Vic, Lan wanted van Hove to take on a well-known work. “I wanted people to see what he could do, and I thought, If they see a play that they think they know, or think they know what it should be like, then they will really see what he is capable of,” Lan told me. He also wanted English actors to play the inhabitants of Red Hook, Brooklyn. “English theatre is often tentative, hesitant, commercially driven, wanting to be loved,” he said. “If we used American actors, I would be apprehensive that people would say, ‘Oh, you have to be American to do that.’ ” (A New York audience may take a few moments to adjust to the cast’s accents; van Hove called for them to be generically American rather than specific to Brooklyn. “It is not a historically accurate production,” he told me.)

Miller’s play centers on an Italian-American longshoreman, Eddie Carbone, who becomes suspiciously hostile when one of his immigrant relatives expresses romantic interest in his niece. Versweyveld recalls telling van Hove not to dismiss it: “I said, ‘I see a lot of layers: the incest relation, the matrimonial relationship, the workers from Italy, the poor who come to a rich country.’ ” Eventually, van Hove established some personal connections with the text. The milieu of Italian immigrants coming to work in a foreign country reminded him of his home village, where Italian neighbors filled the mining jobs that Belgians disdained.

Versweyveld’s set is an enclosed square space, like a boxing ring. It alludes to the footprint of a row house in Red Hook. “It is a house, but it is a ruin of a house, almost like Pompeii,” van Hove told me. “It is a house that has been. You see a wall, a door—you can imagine there has been a kitchen, a table, but it is all gone.”

The rehearsal process was an unusually intense three weeks. The original plan had called for five weeks—already a tight schedule. “Then I get this phone call from Ivo saying, ‘David, I have completely fucked up, I forgot to tell you I am going to be in Australia the beginning of the second week of rehearsal,’ ” Lan told me. “I said, ‘Well, you do the first week, and then you go to Australia.’ He said, ‘Look, I have got a better idea. I won’t do the first week, or the second week, either.’ It was the only time he got a bit cross with me. He said, ‘You have to trust me. Now you are coming into my territory.’ ” In the middle of tech rehearsals, with previews only days away, van Hove informed Lan that he needed to make a trip back to Amsterdam. “I thought to myself, O.K., there is something else going on here,” Lan said. “He doesn’t want the time.”

The actors worked in an empty studio. “In another room, we had all the props, but the actors didn’t know it,” Versweyveld said. Mark Strong, who plays Eddie Carbone, told me, “The first day, we all arrived and said hello, and were shown a model box of the set, with the absence of furniture. We all kind of looked at each other and went, ‘Oh-kaaay.’ But, as time went on, if they told you a prop was unnecessary you began to tell that they were right. There wasn’t any need for props.” About a week into rehearsal, Strong said, van Hove commanded the cast to go barefoot: “Ivo said, ‘We don’t need shoes,’ and we took them off, and we never thought about them again.” Initially, a knife was brought out for the climactic fight between Eddie and his wife’s cousin Marco. “But it just seemed absurd,” Strong said. In the show, the battle is staged without a weapon: there is just a bloody, obscure clashing of bodies, a nightmare out of Caravaggio.

“I just wonder if yet another pincer movement might be just what they are expecting.”

On Broadway, as in the West End, the most prized seats may be those which are set up onstage, on either side of Versweyveld’s arena, almost within reach of the actors. “You really felt as though at any moment Eddie Carbone could come off that stage and grab your throat,” Joe Melillo told me. “It was, like, ‘Oh, my God, I am given license to be a witness to a murder. I am really going to see someone kill someone.’ ”

In September, van Hove was back at the Young Vic with a smaller production: “Song from Far Away,” a one-man play by the young British playwright Simon Stephens. It was written specifically for Eelco Smits, who first performed it, in English, earlier this year in São Paolo. Van Hove rarely directs a new work. He doesn’t like to commission plays, for fear of receiving something that he doesn’t like and then feeling obligated to present it.

Stephens had spent a week in Holland, at van Hove’s invitation, and had devised a story about a young Dutch banker, living in New York, who returns to Amsterdam after the unexpected death of his brother. Smits had performed “Song” in Amsterdam, in Dutch, a few weeks earlier. For the London production, which was in English, van Hove had scheduled only a few days of rehearsal before the play’s first preview. The show is emotionally and physically demanding: Smits spends forty-five of the play’s seventy-five minutes naked, his nudity underscoring his character’s vulnerability. “It’s what you want to do, because you feel that what Ivo creates, and what Jan creates, is at that level,” Smits told me in London. “It is taken to a certain point, at which you don’t want to say, ‘Can I keep my underwear on?’ You don’t want to be that actor—you want to go there.”

As the crew readied the stage for a run-through of the play, van Hove sat on one of the upholstered benches that had been set up for the audience. He had been busy since I’d seen him working on “Kings of War.” In Amsterdam, he had been rehearsing a new play, and, for once, it was based on a Dutch source: a novel, from 1900, titled “The Hidden Force.” Set in the colonial East Indies, the book was written by Louis Couperus, whom van Hove compares to Thomas Mann. In New York, he’d been casting for “Lazarus,” the Bowie project, and for “The Crucible.” Despite the logistical demands of mounting so many works in succession, van Hove anticipated the exposure with pleasure. “I want to make the most extreme, personal theatre, but for as big an audience as possible,” he said at one point. “I am not the kind of theatre-maker who likes it for small audiences. I don’t do something to please, or to entertain. I don’t think theatre is there for entertainment, purely.”

Van Hove told me that he and Versweyveld had already devised the “universe” in which “The Crucible” was to take place, and that he had been working with his dramaturge to tease out deeper implications from the text. To explain his process, he laid his hands on the bench in front of us. “If this bench would be a play, I would look at it first in total, and I would say, ‘Wow, there is something that is striking here’ ”—he stopped at the brass plaque naming a sponsor—“and say, ‘Look, this one has a name, but they do not all have names.’ And then I would take this backrest down, and unscrew it, and see what is inside. I would undo it, and then put it back together again.”

His preliminary dismantling of “The Crucible” had highlighted some of the themes that it shares with “A View from the Bridge.” Van Hove remarked, “It is very strange—in both plays, at a certain moment, the leading character says, ‘I want my name.’ Your name is your identity, and you don’t want to lose your identity in society. You don’t want to be pushed aside into the margins of society. You want to be at the center of society. And that need, that urge, is also deep in me.”

The house lights went down. Although preparations were still under way, the voices of the crew dropped. “That’s the beauty about theatre—it can be silent suddenly,” van Hove said, with a slight smile. Nonetheless, he continued to speak.

“Before we discuss destroying the competition, screwing our customers, and laughing all the way to the bank, let’s begin this meeting with a prayer.”

“With ‘The Crucible,’ I want to make you believe,” he continued. “For instance, the hysterical outbursts of the girls. I want to make it really frightening.” Miller has a reputation as a moralist who wants to make his opinions about the characters clear. “I want to try not to do that, so that you can make up your own mind at the end,” van Hove said. “For me, it is not a play about good and evil. It is about evil within goodness, and goodness within evil.” He spoke about the character of Abigail Williams, a teen-ager who accuses others of witchery in order to avenge her spurning by John Proctor. “Abigail—she is in pain,” he said. “She is not an evil person. Abigail wants to be somebody, and a girl cannot be somebody in this society. This is the way that I think about it: this society, which seems to be a society, is a bunch of individuals with totally different stories.”

“Ivo?” Versweyveld called from the darkness.

“Yes?” van Hove responded. The crew was ready to begin the run-through of “Song from Far Away.”

The monologue, van Hove told me at one point, was informed by Stephens’s observations about Amsterdam, such as the habit among the Dutch of leaving their curtains open to the street. “I always close my curtains,” van Hove said. “I don’t want people to look inside, because I have a lot to hide. The Dutch, being Calvinist, don’t look inside one another’s windows.” He smiled. “I always look inside. I cannot hold myself back from looking inside.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com