A little over a day after Democrats’ brutal defeat in the Virginia governor race, a bipartisan consensus was already emerging about what happened: Republican Glenn Youngkin’s message about the evils of “critical race theory” in schools crushed Democrat Terry McAuliffe.

Chris Rufo, one of the most prominent anti-CRT activists, has been taking victory laps on Twitter. “Glenn Youngkin made critical race theory the closing argument to his campaign and dominated in blue Virginia,” he writes. “We are building the most sophisticated political movement in America — and we have just begun.”

His critics agree. MSNBC’s Nicole Wallace said on air that “critical race theory, which isn’t real, turned the suburbs 15 points to the Trump-insurrection endorsed Republican.”

Even some nonpartisan analysts, like NPR’s Domenico Montanaro, credited the campaign against education on systemic racial issues with Youngkin’s win. “Democrats have to come up with a convincing way to answer the (often false) charges about how children are being taught about structural racism in schools,” Montanaro writes. “Youngkin rode that wave and owned the issue.”

The critical race theory-focused analysis is convenient for both Republicans and Democrats. For the former, it’s proof that they’re on the winning side of America’s seemingly endless culture wars. For the latter, it’s more evidence that Republicans are the party of white backlash and anti-Blackness.

There’s one problem: The evidence for this conclusion is surprisingly weak.

It is true that exit polls showed education and critical race theory as important issues to Virginia voters. But exit polls, in addition to generally not being super reliable, are not a very good gauge of what actually swung races: Among other reasons, partisans who would have voted for their party anyway often parrot whatever message they heard from the campaign or allied media. And when you zoom out, the pattern of the night’s results is not consistent with a CRT-focused explanation.

Related

What the hysteria over critical race theory is really all about

The election returns from Virginia show a uniform swing against McAuliffe, not an especially strong backlash in areas where CRT was an especially prominent issue. In New Jersey’s gubernatorial race, there was a similarly sized swing against Democrats despite CRT not being a major part of the campaign.

A broader look at election night on November 2 tells a different and more familiar story: McAuliffe lost because of a nationalized backlash against an unpopular incumbent president.

The anti-Biden interpretation is consistent with the history of Virginia’s elections, where the party controlling the White House has lost 11 out of the last 12 times, as well as a deep body of political science research finding that the electorate tends to swing against a president’s party in off-year and midterm elections.

“We tend to see electoral swings against the party of the president after they’re in office [and] people tend to overattribute those swings to the idiosyncratic features of a single race or their own pet issues,” writes Robert Griffin, the research director at the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group. The CRT-focused interpretation of Virginia’s election fits Griffin’s pattern.

The narrative of fears over critical race theory driving votes could still turn out to be correct; it’s difficult to be fully confident about election results 48 hours after they happen.

But the discourse doesn’t wait for full evidence before coming to conclusions. The lessons political observers take from Virginia’s elections in the coming days and weeks will shape the way the two parties set their strategies for 2022 midterm elections.

And based on what we can see so far, a dominant narrative about Virginia emerging among partisans on both sides rests on thin evidence.

What we know about the role of critical race theory in Virginia’s election

Critical race theory was, until recently, an obscure school of thought in legal academia focused on analyzing the failures of mainstream legal approaches to fully remedy racial inequalities embedded in American law and society. It is not a standard part of the K-12 curriculum in Virginia or elsewhere.

Nonetheless, conservative intellectual entrepreneurs like Rufo have succeeded in redefining the term “critical race theory” to refer to a whole swath of progressive trends in sociocultural life, ranging from diversity trainings to history curricula emphasizing the role of racism in American history.

Some of these trends may owe an intellectual debt to CRT proper, but many of them do not. Regardless, the catch-all label has proven politically effective. Dark money conservative activist groups in Virginia and elsewhere have rallied angry parents to school board meetings. At least seven states have passed legislation banning the teaching of critical race theory in public schools.

Near the end of the campaign, anti-CRT messaging showed up in Youngkin’s stump speech, where he vowed to “ban critical race theory on Day One,” and became a staple of Fox News reporting on Virginia. A CNN exit poll found that education was the second-most important issue for Virginia’s voters; a Fox exit poll found that 25 percent of voters cited CRT as “the single most important factor” in determining their votes. McAuliffe’s bungled attempt to respond to Youngkin’s attacks — saying “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach” during a debate — certainly didn’t help him.

Combine all that, and it tells a tidy story: Republican activists and aligned media have succeeded in creating a national movement against CRT, one that rallied the right-wing base and flipped nervous white suburbanites who voted for Biden back into the Republican column.

“This was the Chris Rufo Election,” as the writer Noah Smith put it. “Chris Rufo-ism was what won this election.”

Look deeper, however, and the story becomes much more complicated.

Youngkin’s message wasn’t nearly as laser-focused on critical race theory as the commentariat suggested. My colleague Andrew Prokop watched his television ads and found that they didn’t really focus on the issue at all, instead covering issues like crime and Covid-related school shutdowns. CRT was featured in rallies and Fox News, venues that reached the base, but it was not necessarily his broader message to a blue-leaning state.

“Youngkin’s TV campaign is doing the kind of things that you’d think a Republican would want to do in order to compete in [Virginia], certainly much more than the Twitter Trump/cultural war stuff makes it seem,” the New York Times’s Nate Cohn wrote on Twitter.

For the anti-CRT campaign explanation of Youngkin’s win to work, you would expect him to do unusually well in red parts of the state, where more voters were getting the message about CRT, and in areas where local activists on the issue were especially visible (like Loudoun County).

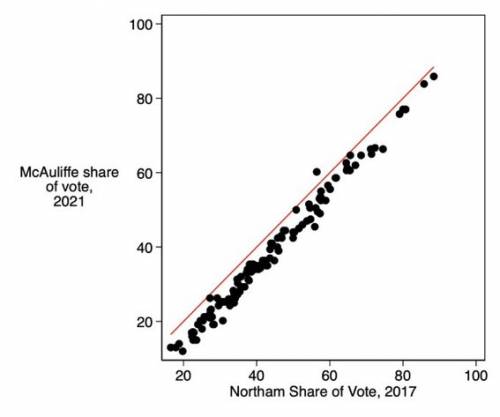

But that’s not what happened. Take a look at this chart from Seth Masket, a political scientist at the University of Denver. It plots McAuliffe’s 2021 performance in different parts of the state against incumbent Gov. Ralph Northam’s 2017 victory, and finds a uniform shift — with nearly every part of Virginia moving in the GOP’s direction to a roughly similar degree.

This suggests, according to Masket, that the outcome “had little to do with sophisticated targeting.” Youngkin didn’t win because he ran up the score in areas where voters heard a lot about CRT; he won by doing better everywhere, with a statewide message that was a lot less immersed in culture war themes than you’d expect.

“If we had seen a massive swing in Loudoun County, which was ground zero for the critical-race-theory issue, that would suggest the Republicans have an issue they can latch on to and use to really pound the Democrats in the midterms,” Sean Trende, RealClearPolitics’ senior elections analyst, told the New Yorker. “But, for now, it looks like if Republicans are going to win, it will be by virtue of not being in power, rather than having some agenda the public is lining up behind.”

The exit polls showing a focus on education and critical race theory aren’t necessarily compelling evidence against this explanation. In general, early exit polls have serious reliability problems that undermine our ability to draw significant conclusions from them. And issue polling often reflects what partisans have heard more than their reasons for voting: Many of the people who said CRT was important were likely going to vote for Youngkin no matter what and latched on to CRT as an explanation.

We have a good test of this theory in the 2021 elections: comparing Virginia to the New Jersey gubernatorial race. In that state, bluer than Virginia, incumbent Gov. Phil Murphy barely hung on against Republican Jack Ciattarelli. Given that New Jersey is more Democratic than Virginia, these results suggests GOP gains that were roughly similar in each state, maybe even larger in New Jersey — despite some notable differences in campaign topics.

“New Jersey campaign was not particularly culture war focused, was a less salient and lower turnout election, was less about ties to Trump and national leaders, and resulted in a similar swing rightward,” writes Matt Grossmann, a political scientist at Michigan State.

None of this is to say that education didn’t matter at all in the Virginia outcome. It’s way too early to make that kind of sweeping conclusion, especially when there’s good reason to believe that parents’ frustration with Covid-related school closings were a real factor in 2021.

Rather, it’s to say that the narrative that CRT was decisive in the Virginia election is not especially consistent with the evidence available right now.

The “thermostatic” explanation — and why it matters

In 1995, political scientist Chris Wlezien developed what’s called the “thermostatic” model of American politics. The idea is to think of the electorate as a person adjusting their thermostat: When the political environment gets “too hot” for their liking, they turn the thermostat down. When it gets “too cold,” they turn it back up.

In non-presidential elections, this means that voters swing back and forth in response to who’s in power — moving to Democrats when the system is controlled by Republicans and vice versa. The party out of power has an easier time motivating its base voters to turn out and rallying public opinion against policy overreach by the White House.

The thermostatic model has a lot of empirical support. It can explain why the president’s party almost always tends to lose seats in midterm elections, why 11 out of the last 12 Virginia governor’s elections have been gone against the party in power, and why Phil Murphy is the first New Jersey Democratic governor reelected since 1977 (and barely at that).

The simplest explanation of Virginia’s and New Jersey’s results is that we’re seeing thermostatic preferences at work. Republicans are angry that Democrats are in power, and Democrats are less excited with Trump out of the White House.

“Enthusiasm matters in elections. In VA, Youngkin got 84% of Trump’s 2020 vote [while] McAuliffe just 65% of Biden’s,” Amy Walter, the editor-in-chief of the Cook Political Report, wrote on Twitter.

Structural factors, like thermostatic public opinion or economic conditions, tend to be far more important in American elections than tactical choices by campaigns — which, generally speaking, only matter at the margins. What Youngkin said about CRT is probably less important than the fact that he was running as a Republican in 2021.

Of course, the thermostat doesn’t control everything. Much like a heat wave can overcome your air conditioning system, extreme events can overcome the normal dynamics of American elections. After the 9/11 attacks led to a surge in George W. Bush’s approval ratings, Republicans made gains in the 2002 midterms.

No similar event has buoyed Biden’s approval rating — in fact, it’s been quite the opposite. Negative media coverage of the Afghanistan withdrawal, Democratic infighting surrounding Biden’s economic agenda, and the pandemic’s persistence all seem to have taken a serious toll on the public’s perception of the Biden administration. Virginia Democrats would’ve already faced an uphill battle with a Democrat in the White House; that the Democratic president is now especially unpopular explains a lot about the November 2 results.

How those results are interpreted, and which narratives take hold, matter because they shape the way the parties respond. They don’t have time to wait for a dissertation on the results to be published, and work with the limited information they have now.

“And now the real politics begins —the politics of explanation,” Georgetown’s Matt Glassman wrote after the race was called for Youngkin. “The bivariate result is obviously very important, but perhaps more important is how other officials — elected and not, in VA, in Washington, and elsewhere — understand it, and alter their actions.”

In a way, it’s convenient for both parties to believe the narrative about CRT swinging Virginia’s election: It flatters their ideological priors and suggests that they can do better by doing something as simple as adopting a new set of talking points. But the best evidence we have suggests they might be drawing the wrong conclusion.

Will you support Vox’s explanatory journalism?

Millions turn to Vox to understand what’s happening in the news. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower through understanding. Financial contributions from our readers are a critical part of supporting our resource-intensive work and help us keep our journalism free for all. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today to help us keep our work free for all.

Sourse: vox.com