Birthdays are important to Marina Abramović, the performance artist who was born in Belgrade, the capital of what was then Yugoslavia, on November 30, 1946. The body is her subject, time is her medium, and birthdays mark the moment that the performance of living officially begins. Abramović has never been shy about her age—when she turned sixty, she celebrated with a black-tie gala at the Guggenheim Museum—and age has been kinder to her than she has ever been to herself. You would recognize her today from the grainy photographs of her earliest performances, forty years ago, when she was a dark, offbeat girl with sad eyes and chiselled features in a pale face. Perhaps it was too expressive a face to be pretty—the obdurate and the yielding at odds in it. But some charismatic women, like Abramović, or her idol Maria Callas, are beautiful by an act of will.

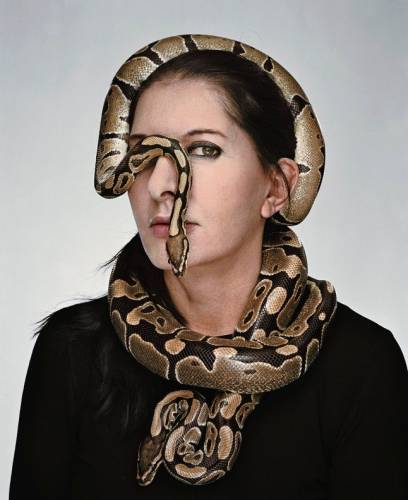

The artist stages her fears, she says, to transcend them.Photograph by Martin Schoeller

At sixty-three, Abramović radiates vitality and seduction. Her glossy hair spills over her broad shoulders. When she isn’t dressed for exercise or the stage, she is likely to be wearing designer clothes. She is fleshier than she used to be, and her body has a different kind of poignance than it did in her waifish youth, but she still has no qualms about subjecting it to shocking trials. In 2005, thirty years after she first staged “Thomas Lips” in an Austrian gallery (Thomas Lips was a Swiss lover whose androgyny had fascinated her), she revived the performance, protracted from two hours to seven, in the Guggenheim rotunda, as part of a show called “Seven Easy Pieces.” The program notes for the original read like the recipe for a banquet dish that would have pleased de Sade:

I slowly eat 1 kilo of honey with a silver spoon.

I slowly drink 1 liter of wine out of a crystal glass.

I break the glass with my right hand.

I cut a five-pointed star on my stomach with a razor blade.

I violently whip myself until I no longer feel any pain.

I lay down on a cross made of ice blocks.

The heat of a suspended heater pointed at my stomach causes the cut star to bleed.

The rest of my body begins to freeze.

I remain on the ice cross for 30 minutes until the public interrupts the piece by removing the ice blocks from underneath me.

Last August, Abramović invited me to observe a five-day retreat that she held at her country home in the Hudson Valley. The main house, built in the nineteen-nineties, sits on a rise overlooking some twenty-five acres of meadows, orchards, and woodland. Its design was inspired by a star-shaped castle on the Baltic. Abramović bought the property in 2007. Even though the star has six points, and the Red star that dominated her childhood, and which figures prominently in her iconography, is a pentagram, she felt that destiny had led her to it. The décor is minimal—a few modern sofas and chairs in bright colors—and the walls are bare. Until recently, she spent weekends here with her second husband, Paolo Canevari, an Italian sculptor and video artist seventeen years her junior. They met in Europe, in 1997, and divided their time between her canal house in Amsterdam and his apartment in Rome. In 2001, they moved to a loft in SoHo. After twelve years together, two of them married, they divorced last December. For the first time, Abramović has learned to drive. “I did it to be independent,” she explained. Her timidity and ineptitude behind the wheel seem incongruous in the character of a daredevil, but, she added, “I have always staged my fears as a way to transcend them.”

The retreat was an intensive workshop in hygiene and movement that Abramović calls “Cleaning the House.” She has taught performance art on several continents, and she has often used Ayurvedic, shamanistic, Buddhist, Gurdjieffian, and other holistic or ascetic practices to initiate her students. The participants were thirty-two of the thirty-nine mostly young men and women whom she had chosen to participate in a full-scale retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, “Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present”—the first such honor for a performance artist—which opens on March 14th. They will be reënacting five of the approximately ninety pieces that she has created since 1969, including three that were originally performed with the German artist Ulay (Frank Uwe Laysiepen), her former lover and collaborator. “Imponderabilia,” a joint work of 1977, will include live, indeed interactive, nudity—another first for the museum. It involves a naked couple planted like caryatids on either side of a narrow doorway at the entrance to a gallery, their backs to the frame. Everyone who enters must sidle past them, deciding which body to face. MOMA will provide an alternative access to the space, an accommodation that Abramović thinks is a pity. Her role as an artist, she believes, with a hubris that can sound naïve and a humility that disarms any impulse to resent it, is to lead her spectators through an anxious passage to a place of release from whatever has confined them.

Abramović’s career falls into three periods: before, with, and after Ulay. He was the son of a Nazi soldier, born on November 30th—Marina’s birthday—in 1943, in a bomb shelter in Solingen, an industrial city in Westphalia that has always produced Germany’s famously superior cutting implements: first swords, then knives and razors. By fifteen, he had been orphaned, and was fending for himself. Abramović met him on November 30th, in 1975. A gallerist in Amsterdam asked Ulay to drive her in from the airport, and to help with the logistics of filming “Thomas Lips” for Dutch television. Their chemistry was immediate. Her first impression was of a tall figure, rock-star skinny, and flamboyantly strange. “He has a heart face,” she recalled, alluding to its double-sidedness. “Half is a tough guy, unshaved, short hair; half has makeup, long hair, and, like me, he wears chopsticks in it.” Ulay’s art, until then, had consisted primarily of Polaroid self-portraits that documented his experiments with mutilation—piercing, circumcision, tattoos—and an obsession with twinship: a male/female duality. That night, after a Turkish dinner—he showed her his diary at the restaurant, she showed him hers; they had both torn out their birthday page, which she took as a karmic sign—she told me, “We go straight to his house and stay in bed for ten days.” She added, “Back at home, I get so lovesick I cannot move or talk.” She was married, at the time, to a former fellow-student from the Belgrade Academy of Fine Arts, but it was an oddly slack union. Both spouses still lived with their parents, and Abramović had a strict curfew: ten o’clock. (They divorced in 1977.) Her mother called the police when Marina “ran away” a few months later, at twenty-nine, to rejoin her soul mate.

Abramović and Ulay made art symbiotically for twelve nomadic years, from 1976 to 1988. They spent one of them living with Aborigines in the Central Australian desert. Amsterdam was their base, but their home on the road, in Europe, was a black Citroën van, which figured in their performance of ideal couplehood. It miraculously survived the beatings it took, and is part of the MOMA retrospective. Their union was also much battered and repaired, though it ultimately couldn’t survive the demands of such intense proximity, of primal wounds, or a discrepancy in ambition that Ulay suggested in an e-mail. “It is very important to understand how much Marina invests in her artistic career, it being her life,” he wrote. That is “one of the reasons why she never wanted to have children.” Their parting was wrenching for Abramović, whose nerves can defy almost any blow except for abandonment. She still believes in true love, and she dispenses affection with a lavishness as intense as her craving for it. But, she reflected, “people put so much effort into starting a relationship and so little effort into ending one.” On March 30, 1988, they embarked on their last performance. She started walking the Great Wall of China from the east, where it rises in the mountains, and Ulay set off from the west, where it ends in the desert. After three months, and thousands of miles, they met in the middle, and said goodbye.

Grace and stamina were prime criteria for the “reperformers” Abramović had chosen for the retrospective, and, judging from their looks, so was the kind of ethereal shimmer that painters once looked for in models for sacred art. Many are dancers; some teach yoga or Pilates; others are performance artists eager to début at MOMA, and to work with a master. They arrived on a chartered bus, and Abramović greeted each of them with a maternal kiss, then confiscated their cell phones. They had signed a contract that obliged them to observe complete silence; to fast on green tea and water; to sleep on the hard floor of an old barn; and to submit to her discipline, which is partly that of a guru, partly of a drill sergeant. (Her drills included practice in nostril flushing and tongue scraping, and a health-food cooking lesson, complete with recipes, which the fasting disciples copied dutifully into their notebooks.) The weather was perfect for a New Age boot camp—hot and dry—and, after breathing exercises in a circle, the troupe filed down to the banks of an icy kill that runs through the property, where everyone, including Abramović, stripped for a communal swim. Divestment in a larger sense—of comfort, modesty, impatience, habits, and attachments—seemed to be what she was after. One afternoon, everyone assembled in an orchard behind the house to await her instructions. She told them to begin moving in slow motion; she would let them know when three hours had elapsed, but until then they couldn’t stop. I watched from a window for a long time as the sun elongated their shadows, and they seemed to become part of the landscape. My own metabolism slowed down with them, and things hidden from a restless eye revealed themselves. I could almost see the apples ripening.

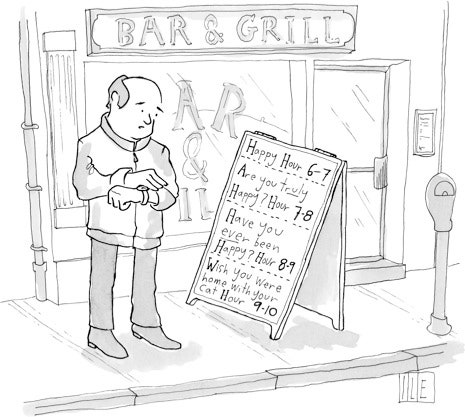

While Abramović’s stand-ins are performing, in rotating shifts, on the sixth floor of the museum, she will present a new work, “The Artist Is Present,” in the Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium. From opening time to closing—eight to ten hours a day—for seventy-seven days, until the show ends, on May 31st, she will sit immobile at a bare wooden table, gazing fixedly into space. Her original concept for the piece involved an elaborate scaffold and props, but as she refined it with Klaus Biesenbach, a close friend and MOMA’s chief curator at large, its showy elements and verticality were discarded. “I made a huge mistake in ‘The House with the Ocean View,’ ” she said, referring to her performance at the Sean Kelly Gallery, in Chelsea, eight years ago—“to put myself up on some kind of altar.” For twelve days, Abramović confined herself to three stark, open-sided cubes, cantilevered to the walls, about five feet above the floor. She could walk between them, and each one had a ladder that she never used—the rungs were knives with the blades upturned. Towels, fresh clothing, water, and a metronome were her only provisions. The gallery was dim, but the “house” was spotlit. Here she sat, lay, stood, stared, stretched, slept, showered, urinated, and fasted in silence, always on view. Some spectators came to ogle her through a telescope she had set up near a back wall, others to keep a reverent vigil. “In every ancient culture,” she went on, “there are rituals to mortify the body as a way of understanding that the energy of the soul is indestructible. The more I think about energy, the simpler my art becomes, because it is just about pure presence.”

“The Artist Is Present” will be the longest durational work ever mounted in a museum. (The artist Tehching Hsieh spent a year caged in his Tribeca studio.) Members of the audience may participate by sitting in a chair opposite Abramović’s. She is hoping for an “emotional connection with anyone who wants to look at me for however long,” but Biesenbach is worried about the show’s unique unpredictability. “It’s an experiment that has never been tried before, and we don’t know what will happen,” he said. If past performances are a guide, some spectators will accept Abramović’s invitation to “exchange energy” with her as they might line up for Communion, although Biesenbach hinted that “people from Marina’s past” might be plotting to surprise her. “What you can and can’t control is part of the piece,” Abramović said. “Electricity fails, nobody shows up—doesn’t matter. If you are not one hundred per cent in the now, the public, like a dog, knows it. They leave.”

The one given is the “enormous bodily pain” that Abramović knows she will suffer—“especially at the beginning. Motionless performances are the hardest.” Pain is the constant in her art. (Only rarely has she aborted a performance, although once the audience intervened to save her life. This happened in 1974, at the Student Cultural Center in Belgrade, where she performed a piece called “Rhythm 5.” She lost consciousness inside the perimeter of a burning star, and was dragged to safety.) She has screamed until she lost her voice, danced until she collapsed, and brushed her hair until her scalp bled. In an early piece, she ingested anti-psychotic drugs that caused temporary catatonia. She and Ulay traded hard slaps, hurled themselves at solid walls, and passed a breath back and forth, with locked lips, until they fainted. He pointed an arrow at her heart as she tensed the bow. These performances were works of dynamic sculpture, with a formal rigor and beauty, but what, I asked her, distinguished their content from masochism? “Funny, my mother asked the same question,” she replied. “All the aggressive actions I do to myself I would never dream of doing in my own life—I am not this kind of person. I cry if I cut myself peeling potatoes. I am taking the plane, there is turbulence, I am shaking. In performance, I become, somehow, like not a mortal. All my insecurities—having a fat body, skinny body, big ass, long nose, a guy, being abandoned, whatever—aren’t important.” What makes it art? Context and intention, she said: “The sense of purpose I feel to do something heroic, legendary, and transformative; to elevate viewers’ spirits and give them courage. If I can go through the door of pain to embrace life on the other side, they can, too.”

Some people inflict pain upon themselves in order to replay—and to master—cruel treatment that they once endured helplessly. Abramović’s mother, Danica Rosić, was born into a clan of great wealth, power, and piety; her uncle was the patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Marina’s father, Vojin Abramović (known as Vojo), came from a large and poor family. He and Danica, both Montenegrins, joined the Communist partisans, in 1941, and fought on the front lines. After the war, their service was rewarded with high positions in Tito’s government. Vojo was appointed to the Marshal’s élite guard, and Danica to direct an agency that supervised historic monuments and acquired art works for public buildings. (In the sixties, she headed Yugoslavia’s Museum of Revolution.) The perks of office included foreign travel, a seaside villa, and a huge apartment in the capital, which had been confiscated from Jews during the Nazi occupation. Danica furnished it ornately, and her maids, her husband, and her children (Marina’s brother, Velimir, a prominent philosopher, was born in 1952) were strictly prohibited from touching a thing. “We were Red bourgeoisie,” Abramović said.

Marina’s relations with her mother were always fraught. Danica and Vojo were a volatile couple who slept with loaded pistols and quarrelled violently over his philandering. Danica, who beat Marina for willful, attention-seeking behavior, lived by a Spartan code of “walk-through-walls” Communist determination, as her daughter has put it. “I learned my self-discipline from her, and I was always afraid of her,” she told me. In an interview with her mother that Abramović filmed for a theatre piece titled “Delusional,” Danica reflects on the experiences that steeled her character. “As for pain, I can stand pain,” she concludes. “Nobody has, and nobody ever will, hear me scream.” She demanded the same ostentatious stoicism from her daughter, and she was indifferent, if not unsympathetic, when Marina developed the kind of incapacitating migraines that she herself suffered. An astute new biography, “When Marina Abramović Dies” (M.I.T.; $27.95), by James Westcott, who was once Abramović’s assistant, suggests that these bouts of agonized solitary confinement in her body are a taproot that she draws on both to create and to endure her performances.

Danica, however, nurtured her daughter’s art. Despite her severity, she had a penchant for the kind of genteel “cultural grooming” that a girl of her class would have received before the Communist era. (“My father hates opera, hates Russian ballet, likes to drink with old partisans,” Abramović told me. “My mother is everything about education. I have a piano teacher, English teacher, French teacher, all books are like Proust or Kafka.”) On June 11, 1963, Marina was looking forward to her first foray from home without a chaperone—a trip to Paris. She was a lonely sixteen-year-old chess champion with Coke-bottle glasses, a gangly frame, and flat feet (she wore orthopedic shoes), who cried all the time, she said. But she was painting seriously, and Danica, who had cleaned out a spare room in the family apartment so that she could have a studio, arranged the trip as an introduction to French culture. (Marina entered Belgrade’s Academy of Fine Arts two years later, and in the late sixties she was a leader of student demonstrations that resulted in a concession from Tito: the social club for the wives of his secret police was converted into an arts center for avant-garde experiment, where she gave her first performances.)

Half a world away, on a street in Saigon, Thich Quang Duc, a sixty-six-year-old monk, folded his legs in the lotus position and immolated himself to protest the persecution of Buddhists by the Diem regime. His death was photographed by Malcolm Browne, and reported by David Halberstam, who was, he wrote, “too shocked to cry” as the flames consumed the body. Self-martyrdom as a public spectacle had precedents in Asian culture, but Thich’s composure, as he lit the match, and sat serenely for ten minutes of masterly staged agony, rocked the West and burrowed into its collective dream life. “No news picture in history has generated as much emotion around the world,” President Kennedy said.

Abramović says that she never forgot that “terrible image of devotion to a cause,” and in a recent interview Ulay noted that the photographs and film footage streaming out of Vietnam politicized his generation of artists. Thich’s auto-da-fé coincides with the moment that a new genre—an art of the ordeal, spawned by the generational conflicts and social upheavals of the nineteen-sixties—began to gather momentum. Those who practiced it did so, at first, in the name of sabotage and refusal. They were, like the Romantics and the Dadaists before them, assaulting bourgeois complacency, redefining obscenity (as the news did), and rejecting materialism—the production of theatrical illusion, and of art objects that could be commodified. “The knife in a play is only an idea of something that can kill, but a knife in my work is always real,” Abramović said to me. Audiences were asked to witness extreme and sometimes life-threatening rituals that involved self-harm, or that violated deeply ingrained taboos. Performer and beholder shared an aesthetically stylized yet visceral experience in actual time. The more puerile efforts of this school, which was called “body art” (“performance art” or “time-based art” are now the preferred terms), generated a prurient thrill, or just revulsion. The best of them reminded one that there is no voyeurism with impunity.

In 1969, Valie Export (née Waltraud Lehner—she took her alias from a brand of cigarettes) stormed a porn theatre in Munich wearing a pair of crotchless trousers, and brandished a machine gun at the startled patrons, challenging them to engage with “a real woman.” In the early and middle seventies, the Franco-Italian artist Gina Pane lacerated her flesh with thorns and razors. Chris Burden, a Bostonian, arranged to have a friend (an expert marksman) shoot his arm with a rifle at close range, and to be crucified to the roof of a Volkswagen. Vito Acconci, of Brooklyn, masturbated in a crawl space under a ramp at the Sonnabend gallery, as its patrons walked over him. In another New York gallery, Joseph Beuys, a German who had served in the Luftwaffe, cohabited for three days with a coyote. Across the Atlantic, Abramović invited an audience in Naples to probe, soil, bind, tease, disrobe, penetrate, or mark her body, “as desired,” for six hours, using any of seventy-two implements arrayed on a table. They included nails, lipstick, matches, paint, a saw, chains, alcohol, a bullet, and a gun that was, at one point, aimed at her head. “I am the object,” she declared in her program notes. “During this period I take full responsibility.” As the hours passed, she remained utterly impassive, though she couldn’t hold back her tears. A few spectators wiped them away, and, as others began toying with her body, two factions emerged: vandals and protectors. It wasn’t entirely a division by gender. “The women didn’t touch me,” she said, “but some of them egged the men on.” Photographs of this performance, “Rhythm 0,” show Abramović being laid out like a corpse, posed like a mannequin, pinned with slogans, stripped to the waist, kissed, showered with rose petals, doused with water, and hooded like a captive. Someone used the lipstick to write “END” on her forehead.

Abramović’s feminism has always been a mythical, rather than a political, understanding of women’s oppression—and of their power. RoseLee Goldberg, a leading curator and historian of performance art, noted that for American women of Abramović’s generation “being a feminist meant joining the party. That kind of solidarity—or of conformity—signified something different to Marina. By the time she became an artist, she wanted freedom on her own terms. And I always saw her in the pieces with Ulay as being in charge.”

Abramović has often commented on the irony that her birth certificate bears a Red star, while Ulay’s has a swastika. That is the conflict—between Communism and Fascism—that shaped her world view. But in 1997, twenty-three years after her ordeal in Naples, she returned to Italy for an act of engagement with contemporary history. It was two years after the Dayton Peace Accords, and the Montenegrin minister of culture had invited Abramović, the child of national heroes, to represent their native country at the Venice Biennale. Sean Kelly, her gallerist, advised her to decline, on the ground, Westcott writes, that “she shouldn’t risk the perception” of complicity with Slobodan MiloSevic´. (Serbia and Montenegro were then a federation; they are now independent.) She, however, was determined to participate. Even though “she recognized Serbia’s role as an instigator of the violence,” Westcott continues, “she saw aggression on all sides,” and the invitation was “an opportunity to perform an act of mourning” for the dead on all sides. But when the minister learned of the performance she was planning, and its price tag—about a hundred thousand dollars—he rescinded the invitation with an insulting letter: “Montenegro is not a cultural margin and it should not be just a homeland colony for megalomaniac performances.”

Outraged, Abramović and Kelly asked Germano Celant, a curator of the Biennale, to find her a venue. The only space left was a fetid basement with low ceilings and a concrete floor, in the Italian pavilion. It was perfect for her purposes. The performance that Abramović staged there, “Balkan Baroque,” which won the Golden Lion—the award for best artist—was an expression of her complex shame for, and her attachment to, her identity not only as a Yugoslav but as the daughter of Vojo and Danica. Equipped with a bucket and brush, she spent six hours a day, for four days, abjectly scrubbing fifteen hundred raw cow bones that, in the summer heat, were crawling with maggots. The interview with Danica from “Delusional” and one with Vojo, waving a gun and telling grisly war stories (they were both filmed in Belgrade in 1994, when the city was still an armed camp), were projected on the walls at angles to a video of Abramović, in a white lab coat, explaining a sadistic Serbian technique for killing rats. She, meanwhile, wept as she scrubbed, and sang folk songs of her homeland. The stench, Biesenbach said, was unbearable, but so was the intensity.

Most of Abramović’s peers among the pioneers of what might be called “ordealism,” to distinguish it from tamer or more cerebral forms of Conceptual and performance art, have long since retired from their harrowing vocation, and some died young. Acconci, who stopped performing in 1973 (he turned to architecture), told me, “What I loved about performance was the contract. You say you are going to do something and you carry it out. What I hated about it was the display of self—the personality cult.” He saw Abramović’s “The House with the Ocean View,” he said, “and I had no idea how to enjoy it. Why did she need an audience to validate a private experience? Are the people really into it with her?” He also questions the principle of reperformance, a contentious point in the art world. One party holds that the integrity of time-based art is inseparable from its transience, and that no performance can or should be resurrected. In an app-happy age, this radical embrace of loss has its nobility.

Abramović has been a prominent target for the purists. Even Ulay recently remarked, “I don’t believe in these performance ‘revivals.’ They don’t have the ring of truth about them. They have become a part of the culture industry.” The credo that he and Abramović lived by in the seventies, “art vital,” called for “no rehearsal, no predicted end, no repetition, extended vulnerability, exposure to chance, primary reactions.” Acconci told me, “Marina now seems to want to make performance teachable and repeatable, but then I don’t understand what separates it from theatre.” (In keeping with his principles, however, he lets things go. He gave Abramović permission to reperform a version of “Seedbed,” his masturbation epic, as part of “Seven Easy Pieces,” which also included homages to Beuys, Pane, Export, Bruce Nauman, and her younger self—the martyr of “Thomas Lips.”)

For Abramović, this debate is too esoteric. “In the seventies, we believe in no repetition,” she said. “O.K., but now is a new century, and without reperformance all you will leave the next generation is dead documents and recordings. Martha Graham also didn’t want her dances reinterpreted by other choreographers. I think it is selfish of the artist not to let her work have its own life.” She hopes to raise several million dollars to convert a derelict movie theatre that she bought three years ago, in Hudson, New York, into the Marina Abramović Foundation for the Preservation of Performance Art, with a study and media center, a café, and a hangar-size performance space. At the moment, it is a temporary warehouse for a lifetime’s worth of documents. (The purgative ethos of the retreat does not, apparently, apply to her archives.) In addition to prints, books, and correspondence, she has held on to posters, ticket stubs, yellowed news clippings, props, and souvenirs of her travels. It is quite a payload for a nomad, and the retrospective is adding to it. There is the two-hundred-and-twenty-four-page MOMA catalogue; a book of essays by the art critic Thomas McEvilley, “Art, Love, Friendship: Marina Abramović and Ulay, Together and Apart” (McPherson; $27); and a documentary directed by Matthew Akers, who has been following Abramović since last summer and has filmed hundreds of hours. (He will record every second of her performance.)

The publication of Westcott’s biography also coincides with the show. It tells a riveting story with composure and autonomy, and it gives perspective to a tortured, myth-laden narrative that Abramović herself can’t stop retelling. “The Biography,” created in the early nineties with the videographer Charles Atlas, and its sequel, “The Biography Remix,” with the stage director Michael Laub, are a grandiose unfolding self-portrait. It takes the form of elaborately scripted multimedia spectacles that call for supporting actors, live pythons and Dobermans, colored lights, bondage costumes, a Callas soundtrack, a rehash of old performances, and a voice-over in which Abramović recounts, sometimes in Serbian, the milestones of her life. This extravaganza seems at odds, to say the least, with her ideals of abstinence and spontaneity. Initially, though, it helped Abramović “to get over” Ulay, she told McEvilley, and every few years she adds a new chapter. The next installment, a theatre piece directed by Robert Wilson, “The Life and Death of Marina Abramović,” is in the works.

Last November, Abramović invited a group of old friends to her sixty-third birthday dinner, in her SoHo loft. It is a luxuriously spare, open space with a fashion plate’s dressing room off the master bath—Abramović’s gift to herself after Paolo Canevari moved out. She likes to cook homey meals, and, in the country, she had gathered vegetables from her organic garden to make a soup for the reperformers when they broke their fast. But on this occasion she had hired a chef, a young artist whose menu had an unusual concept: It was dedicated to the victims of Hurricane Katrina. Rum and bourbon were served in paper cups, and after a lengthy cocktail hour the doors to the kitchen were folded back to reveal sixty-three quarts of gumbo in plastic containers. The guests looked somewhat stricken when a posse of couriers arrived to distribute the gumbo to the homeless. While they were wondering when or if something to eat would appear (eventually, it did—okra doughnuts), David Blaine, the magician, did card tricks, and changed the time on Laurie Anderson’s watch from across the room. He is planning his own next feat of ordealism—he will seal himself in a super-sized glass bottle and have it tossed into the ocean. “Marina is one of my greatest inspirations,” he told me. She was in glamour mode, in a clingy black dress and artful makeup, with her hair down. “I want you to meet someone,” she said, and led me to a corner where a giant cherub with a soft, sad face and a dishevelled pageboy was leaning against the wall. “This is Antony. He will, I hope, be singing at my funeral.”

Antony Hegarty, of Antony and the Johnsons, is famous for his otherworldly voice. But it is not just his music, I surmised, that Abramović finds so compelling. His fragility is transparent, whereas she has to suffer in public to make hers visible beneath an Amazonian guise. The song he will sing, when she dies, “if all goes well,” she said, is “My Way.” Then she outlined the program for her farewell performance. It will take place simultaneously in three cities: Belgrade, Amsterdam, and New York. All the mourners will wear bright colors. And in each city there will be a coffin. “No one will know,” she said, “which has the real body.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com