The architects Louise Harpman and Scott Specht began collecting takeout-coffee lids when they were in college, in the nineteen-eighties, and continued the practice as graduate students at Yale. Separately, and unbeknownst to each other, they had amassed, in their dorm rooms, a trove of everyday objects that they found aesthetically pleasing. Specht had glass radio tubes, medicine bottles, and airline-safety cards; Harpman had Ferrara Pan candy boxes, flypaper packaging from the forties, and hot-water bottles. They both had coffee lids. Once they learned of their shared interest, they began comparing notes, like trading-card fanatics.

“There was the Wawa convenience-store lid, the 7-Eleven, the Dunkin’ Donuts,” Harpman recalled. “It was, like, ‘Oh, I found this one, do you have that one?’ ” After they merged their collections and married, they ran an architecture firm, Specht Harpman, for twenty years, until they separated and split their practice. All the while, the coffee-lid collection grew; at some five hundred and fifty lids, it is likely the world’s largest. (In 2012, the Smithsonian acquired a selection. “We only gave them ones we had duplicates of,” Harpman said.) Harpman now teaches at N.Y.U. and lives nearby, and Specht divides his time between New York and Austin. The coffee lids have stayed together, in acid-free boxes, under Harpman’s bed.

On a recent Tuesday, Specht and Harpman, bright-eyed and caffeinated, met at Lafayette, a French café in NoHo, for field research. They had brought with them their new book, “Coffee Lids: Peel, Pinch, Pucker, Puncture,” which includes color photographs and original patent drawings for more than two hundred unique lids. (The subtitle refers to method of access.) Harpman wore a white blouse under a navy cape coat; she had pushed her glasses up into her bob. “The biggest distinction in the taxonomy is whether you peel away part of the lid, so you can actually get your lip on the cup, or, like this one”—she held up her latte—“you drink through the piece of plastic. There’s one I like best, by a designer named Morris Philip, that sits down in the cup.”

Specht nodded. He was wearing a fitted jacket over a dark shirt, and steel-rimmed glasses. “I love the megalomania of that cup,” he said.

In the time before lids (B.L.), when people carrying coffee moved at a slower pace, there was only a rimmed plastic snap-on disk, patented, in 1950, by James D. Reifsnyder, of the Lily-Tulip Cup Corporation. It contained no drinking holes. After the 1983 Dodge Caravan/Plymouth Voyager hit the road, with built-in cup holders, lids like the Solo Traveler, designed by Jack Clements (and now in MoMA’s collection) introduced a small drain, for overflow, in addition to a sipping hole. The field-guide section of “Coffee Lids” includes pages on “Ergonomic Drink Apertures” (“the sippy cup”), “Foam Accommodation Techniques” (“the FoamAroma”), and “Slosh Drainage Systems” (Nyman Manufacturing Company Model 11096: “a mess waiting to happen”).

Harpman mentioned a recent prize. “Last summer, in London, somebody’s walking across the street with this crazy lid.” She fished a Ziploc bag from her handbag.

“The bug-eye lid,” Specht said. It was covered in plastic buttons to indicate the type of drink: choc, cap, special, latte, white, mocha.

“It’s from McDonald’s! ” Harpman said, brandishing the lid. “I’d thought the pinch category was dormant.”

Around the corner, at La Colombe, Specht grabbed two lids from behind the counter while a clerk’s back was turned. “They have the Viora lid,” Harpman said. “This is the one Wired thinks is the best.” It has a thin rim and a recessed space for the nose.

Specht brought up a failed expedition to Gasoline Alley, an upscale, minimalist coffee shop nearby. “Yesterday was unbelievable,” he said. “We walk into the place, and they’re, like, ‘What are you guys doing?’ We told them a bit about our research, and the manager came out and said, ‘We need to call the owner.’ People are so paranoid.”

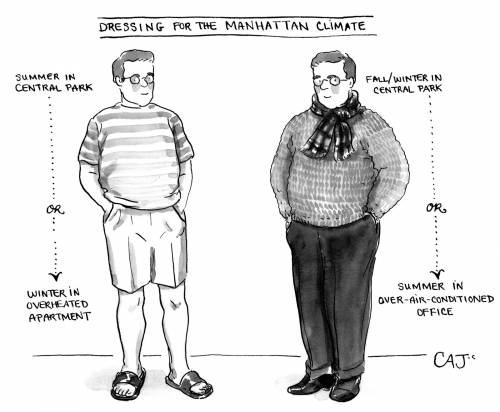

On the street, Harpman pointed out several orange-and-white striped street barricades (“They’re just everywhere”), and counterweighted fire escapes (“Incredibly beautiful”). Specht extolled the menus from restaurants like IHOP, which show photographs of food (“I have a huge basket of those”).

In Think Coffee, a man in a blazer, holding two hot drinks, waited while the pair examined the dimples on the compostable lids. “Decaf, cream, and black—that’s all,” Specht said.

They decided to try Gasoline Alley again, lowering their voices as they entered. Specht took a lid from a shelf. “You’ve got a basic, a generic,” he mused. “This must be gaining leadership.”

“We saw that one at Darkstar,” Harpman noted.

The barista, a bearded man in an apron, had been watching. “I’m not trying to stare,” he said. “Anything I can help you with?”

Harpman gave a friendly wave. “We’re thinking!” she said. They exited quickly. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com